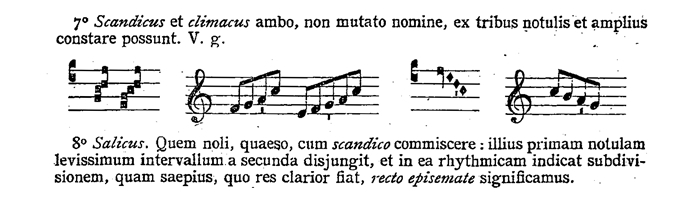

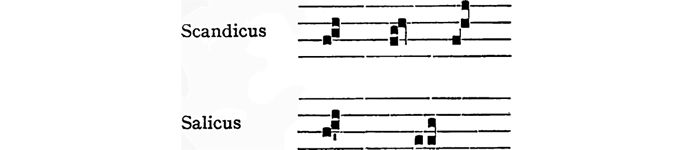

Many singers cannot tell the difference between a Scandicus and a Salicus in the Editio Vaticana:

As you can see, the Salicus can be recognized (with some effort!) because a “thin sheet of paper” could be inserted between the first note and the last two, like so:

As Joseph Gogniat has pointed out:

A little later, he explains in more detail:

Please read all that he has to say about the Salicus on pages 31-32 (PDF). If you have completed the lesson the Vatican Edition, you will understand his final paragraph, noting that if Pothier had added more “white space,” the meaning would be quite different.

Therefore, the Salicus in the Vaticana is fairly straightforward. However, Dom Mocquereau throws us a “curve ball.” Mocquereau has his own definition of the Salicus:

That definition (found in the 1961 Liber Usualis) is, perhaps, more clear and thorough than one given in Solesmes’ Mass & Vespers (1957):

Incidentally, this same definition is given (in Latin) for the 1924 Liber Usualis:

Now let us examine the neum table from Mass & Vespers (below). This table is slightly “deceptive” (for reasons that will be made clear below) in the sense that it puts an ictus on a “true” Vaticana Salicus — in other words, one that you could put a “thin sheet of paper” between:

The reader is encouraged to read what Dom Mocquereau has to say about the Salicus in Le Nombre Musical Grégorien, Pages 401-411 (PDF). When reading, you may notice that Mocquereau also allows the horizontal episema to signal a Salicus:

As a matter of fact, Mocquereau had originally wanted to place horizontal episemata under the Salicus, but he could not, because the Sacred Congregation of Rites forbade him to alter the notes of the Vaticana. This is confirmed by a note in the front of the 1934 Liber Usualis:

As shown below, a horizontal episema works for places where there is a “true” Salicus (as defined by the Vatican Edition), but not for places where the Vaticana marks a Scandicus, but Solesmes wants a Salicus. “1A” shows a Vaticana Salicus. “2A” shows how Mocquereau would have preferred to mark his Salicus. “3A” shows why Mocquereau could not do this. 4A is a “true” Salicus, which Solesmes also marked as one. “5A” is a Vaticana Scandicus which Solesmes calls a Salicus. “6A” is a Vaticana Salicus, which Solemes marks as a Scandicus!

Now, let us observe some actual examples. “1B” shows a Vaticana Salicus which Solesmes pretends is a Scandicus. “2B” is a Vaticana Scandicus which Solesmes pretends is a Salicus. The same can be said about “3B” and “4B”:

There appears to be some confusion in the neum charts when it comes to a “little black line” that connects the Scandicus. I do not believe I have ever seen such a line in the Vaticana, yet even as late as 1924, the Solesmes Liber puts it on the Scandicus:

Joseph Gogniat (Little Grammar of Gregorian Chant, 1939) also seems to imply that such a line is technically possible in the Vaticana, but (again) I cannot recall ever seeing one:

Dom Gregory Suñol (Gregorian Chant According to the Solesmes Method, 1929) gives this little chart, which also seems to imply that the “little black connecting line” is possible in the Vaticana:

Lura Heckenlively (Fundamentals of Gregorian Chant, 1950) does likewise:

Let us now consider a few historical points of interest. The Vatican Edition of the Kyriale was published in 1905, but had no Preface of any kind. The Vaticana Preface was published with the Graduale in 1908. When the Vatican Kyriale appeared in 1905, there was much confusion about how to form the notes. Some day, I would like to document this in a more satisfactory way, as I have collected many different publishers’ versions of the Kyriale from 1905. In any event, let us consider the Preface to Mocquereau’s version of the Vatican Kyriale, published in 1905. The pages have deteriorated over the last century, so I have typed the words in purple:

Then, later on, Mocquereau clarifies what he said about the “white space” of the Salicus:

Incidentally, out of all the Solesmes books I have, this is the only one whose Preface is signed. Mocquereau usually preferred to work incognito. Incidentally, the table above is identical to the one found in the Solesmes Kyriale of 1904, which, apart from this introductory material, differs radically from the Vatican Edition of 1905 (as you might imagine):

Let us consider another interesting item. Dr. Peter Wagner, champion of Pothier’s Vaticana, does not even draw a distinction between the Salicus and Scandicus! What must his student, Gogniat, have thought? In his 1905 Organ Accompaniments to the Kyriale, Wagner prints this:

Perhaps Dr. Wagner was confused by Pothier’s earlier publications, where no distinction was made between Salicus and Scandicus:

Here is an interesting puzzle found in the 1922 Liber Usualis of Solesmes. As you can see, in their introductory notes, they pretend as if their version of the Salicus is identical to the Vaticana Salicus:

However, in the actual piece of music, notice that they are not allowed to alter the spacing:

Finally, it should be noted that in recent years, there have been more and more theories about the Salicus. These theories will treated in a later lesson (since this section is already too long!). In particular, some have suggested that during the 9th century (and later), the Salicus may have been performed with an emphasis on the last note (for groups of three notes). Scholars disagree on this: some have become convinced, while others feel this notion is based in large part on speculation and, while certainly a possibility, cannot be proven in a satisfactory manner. In general, the trend among scholarship has been to stop making generalizations about the entire corpus of Cantus Gregorianus, focusing instead on the local variations of chant performance presented by the myriad of MSS. Another way to put this would be to say that scholarship is moving away from the “authentic source” theory, and looking more and more at the entire tradition (no longer just two or three families of MSS). In fairness, for several decades, many scholars had access only to MSS printed in the Paléographie Musicale, but with more and more libraries putting MSS online, this is no longer the case.

Regarding these new theories about the Salicus, whether one is convinced or not ultimately makes no difference. The question is what impact (if any) these would have on the performance of the Vaticana. After all, the Vaticana never claimed to be an authentic edition of any particular ancient MS. As a matter of fact, Pothier went to great lengths to make clear that the Vaticana is based on the entire chant tradition, and not this or that specific in campo aperto manuscript. Finally, as scholars have known for close to a century, it is without question absolutely true that the notes in the Vatican Edition do not correspond perfectly to individual notes sung in the 8th through 10th centuries, so applying rhythmic theories based on specific MSS from that era is problematic for a whole host of reasons.