OR MANY, anything old is deemed “history.” Since they don’t like history—or consider it boring—everything historical becomes a blur. In the minds of such people, there’s no real difference between 1927, 1860, 1796, and 500AD. To them, it’s all just “old stuff.” But I believe we should have a basic understanding of the era in which something takes place. A fascinating and pivotal historical figure was THEODORE ROOSEVELT (d. 1919). Indeed, he had his fingers in so many different pursuits, it would be impossible to summarize or “encapsulate” his life in a few words, so I won’t try. However, Teddy Roosevelt’s era in America roughly coincides with the creation of the official edition (“EDITIO VATICANA”). Indeed, the Vatican Commission on Gregorian Chant was created by Pope Saint Pius X—cf. Col Nostro—on 25 April 1904, the same year Roosevelt was elected president. Even today, the EDITIO VATICANA remains the official edition of the Catholic Church.

OR MANY, anything old is deemed “history.” Since they don’t like history—or consider it boring—everything historical becomes a blur. In the minds of such people, there’s no real difference between 1927, 1860, 1796, and 500AD. To them, it’s all just “old stuff.” But I believe we should have a basic understanding of the era in which something takes place. A fascinating and pivotal historical figure was THEODORE ROOSEVELT (d. 1919). Indeed, he had his fingers in so many different pursuits, it would be impossible to summarize or “encapsulate” his life in a few words, so I won’t try. However, Teddy Roosevelt’s era in America roughly coincides with the creation of the official edition (“EDITIO VATICANA”). Indeed, the Vatican Commission on Gregorian Chant was created by Pope Saint Pius X—cf. Col Nostro—on 25 April 1904, the same year Roosevelt was elected president. Even today, the EDITIO VATICANA remains the official edition of the Catholic Church.

Historical Context • Some Americans would die before they drank unfiltered water, ate food that’s expired, or purchased something not labeled “organic” from the supermarket. The era of Teddy Roosevelt—or, if you prefer, the era of the EDITIO VATICANA—was quite different. One example: as a young boy Roosevelt was a taxidermist who sometimes kept specimens (such as dead mice) on top of cheese in his parents’ icebox. I doubt Americans would tolerate such a thing today! Indeed, when he was serving as President of the United States, Roosevelt let his children run amok in the White House. They would drop water balloons on the Secret Service, or let loose wild animals at tables where foreign dignitaries were dining. Therefore, when I speak of plainsong edition discrepancies, keep in mind the great advantage we have today over those who lived in those days. Indeed, 95% of Americans in those days would be considered poverty stricken by today’s standards. That’s important! Poverty limited one’s ability to become educated or access important documents. Contrariwise, today’s Americans can access almost every book ever published (!) on a smart phone, without even getting out of bed. I know we believe ourselves to be more “sophisticated” than Catholics of the past, but something tells me our work ethic would compare quite unfavorably to theirs.

Quick Review • We never know who is reading the blog for the first time. That means a “review” will be welcomed by some. Where to begin? Well, let’s recall that the EDITIO VATICANA was issued under Pope Pius X. From the very beginning, the Church explicitly stated that:

“this edition must be considered by all persons as the standard or ‘norm’, so that henceforth any Gregorian melodies contained in future editions of these books are to be made absolutely uniform with the aforesaid standard, without any addition or omission.”

If anyone doubted whether the RHYTHM must be followed, the famous Martinelli Letter (18 February 1910), sent under Pope Saint Pius X made things explicit and absolutely clear. Those who follow the “liturgical books of 1962” will be interested in the final word on this matter, given in DE MUSICA SACRA (“Instruction on Sacred Music”) issued under Pope Pius XII in 1958:

When we consider the other words in that paragraph, we see that “force and meaning” refers to rhythm (not pitch). Notice how the paragraph begins: “The signs, called rhythmica…”

An Example • Now let’s take a look at what happened. My professor at the conservatory used to say: “An example is worth 1,000 words.” Therefore, consider how this ANTIPHON (“O Mors, Ero Mors Tua”) appears in the official edition, published by the Vatican Commission on Gregorian Chant in 1912:

Jeff’s Attempt • Here’s my attempt to sing that antiphon. I follow the singing instructions printed in the famous Preface to the EDITIO VATICANA:

![]()

Dom Mocquereau’s Modifications • Now consider the same antiphon as it appears in editions “with rhythmic symbols added” by Dom Mocquereau:

Below is my attempt to sing that same antiphon according to Mocquereau’s rhythm. I’m sure somebody will criticize my attempt because—as I’ve attempted to explain in the past—those who believe in Mocquereau’s method are never satisfied with any interpretation. Anyway, here goes:

![]()

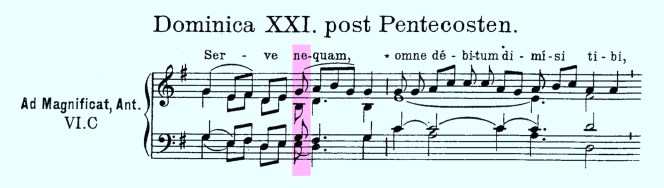

It’s Still Unbelievable • Is anyone willing to step forward and say that Dom Mocquereau’s version respected the “force and meaning” of the official edition? Can we even say that antiphon remained the same piece of music? Dom Mocquereau added thousands and thousands (!) of rhythmic modifications. For example, here’s another antiphon:

What Was His Reason? (1 of 2) • It’s impossible to believe Mocquereau would have supported other publishers doing what he did. Dom Mocquereau wasn’t a stupid man. He surely realized the incalculable damage he was causing to the plainsong’s restoration, which had been carried out by his teacher (Dom Joseph Pothier) at Solesmes Abbey. This restoration had been accomplished against all odds, especially in light of the persecution by the French government against Catholic monks. Why, then, did Dom Mocquereau feel the need to vandalize the official edition? The notion that he was being faithful to the “best” manuscripts is not sustainable—indeed, almost farcical—in light of what we know about the Gregorian tradition. It doesn’t make sense to choose a handful of one’s “favorite” manuscripts and then (having made such a choice) to discard thousands of other manuscripts of tremendous antiquity and colossal importance. Katharine Ellis of Cambridge University (in her 2013 book, The Politics of Plainchant) pointed out what she politely called the “incongruity” between Dom Mocquereau insisting upon hundreds of manuscripts to construct a melody, while at the same time extrapolating rhythmic theories from a minute body of evidence, regarding as “worthless” hundreds of important manuscripts which contradicted his theory.

What Was His Reason? (2 of 2) • Katharine Ellis made a remarkable discovery, suggesting that Dom Mocquereau (who served as Prior of his monastery from 1902-1908) may have had financial incentive to “put as many rhythmic signs as possible in the Graduale and in the Antiphonale.” You can examine this evidence with your own eyes:

It’s also possible Dom Mocquereau never “got over” or “forgave” or “came to terms with” the fact that his project of many years (viz. Liber Usualis of 1903) was passed over by Pope Pius X, who instead ruled that Abbat Pothier’s LIBER GRADUALIS would serve as the basis for the EDITIO VATICANA. My own belief is that Abbat Pothier’s book was chosen because it had a track record of success, whereas the brand new publication by Mocquereau had none. We know that Pope Pius X didn’t like the tiny fonts used by Mocquereau in his 1903 tome. Indeed, on 20 December 1903, the musical advisor of Pope Pius X wrote as follows to Dom Mocquereau’s superior at Solesmes Abbey:

The small books we have at present are completely unsatisfactory for great churches, although most useful for seminaries and colleges. In addition, the Holy Father complained to Dr. Haberl that these books are rather poorly printed in type which is too small, and he advised Herr Pustet to print the chant in larger type. We earnestly beg you, Father Abbat, to restrain the efforts of the excellent Dom Mocquereau and to order that work be started at once on larger books with larger type, as the Liber Gradualis [by Pothier] was originally. The rhythmic signs are certainly excellent for instructional purposes, but since they also present at the very least an occasion for doubt, we earnestly entreat you and beg that … such signs be omitted.

Damage From Mocquereau • I believe that even Abbat Pothier’s protégé was—during moments of weakness—influenced by Dom Mocquereau’s modifications. Consider how yesterday’s Magnificat antiphon appears in the 1932 version by Abbat Pothier’s protégé:

![]()

Why is that elongation added? The official edition doesn’t indicate an elongation there:

![]()

Indeed, the original version by Abbat Pothier certainly does not call for an elongation at that point:

![]()

The edition created in the 1940s by the LEMMENSINSTITUUT handles it correctly:

![]()

I can’t help but wonder whether Dom Lucien David was (inadvertently?) influenced by Mocquereau’s modifications:

![]()

On the other hand, we see the EDITIO VATICANA has a slight “blank” space, although not equal to the width of an individual note head. Was Dom Lucien trying to stress that the first note should be slightly separated from the three which follow?

![]()

Dr. Peter Wagner, Commissionis Pontificiæ Gregorianæ Membrum, seems to “stress” that distinction in his (admittedly deplorable) organ accompaniments:

![]()

Conclusion • My colleague, CORRINNE MAY, told me I need to do a better job concluding my articles—and she was correct. It may come as a shock to readers, but for once my basic point was encapsulated in my title: “Did One Man Single-Handedly Sabotage the Gregorian Restoration?” You can read a similar article by clicking here:

* “Did One Man Sabotage the Gregorian Restoration?” • (Part 1 of 2)

Some will say my article today “does virtually nothing to help the average musician trying to make a difference.” In a certain sense, they’re not wrong. Very soon—hopefully within 72 hours—I will be publishing an article which is much more practical (“helpful”) for the struggling musician. On the other hand, I believe my article today does address something important. Moreover, I hope the examples I recorded make my point in a powerful way.

Heart Of The Matter • To go to the heart of the matter: why was it so easy for people in the 1960s to decimate plainsong in our churches? Part of the problem may have been Dom Mocquereau’s thousands of illicit rhythmic modifications, which caused enormous confusion (since they flagrantly contradicted the official rhythm). Mocquereau eliminated thousands of elongations demanded by the official edition while adding thousands of elongations where they don’t belong. Moreover, the various books explaining Mocquereau’s “ictus” theories made plainsong seem esoteric, abstruse, enigmatic, and (in the end) impenetrable. Plainsong, in my humble opinion, should be simple and natural—excepting, of course, the elaborate “soloist” chants like the tracts, graduals, and alleluias.

Mocquereau’s Maelstrom • Can we lay all blame upon Mocquereau’s maelstrom, which was all the more tragic because it was completely unnecessary? I cannot answer that. It’s certainly true that Monsignor Hannibal Bugnini (d. 1982) had a particular hatred for the Church’s treasury of sacred music. To Father Pasqualetti, Bugnini said: “sacred music remained the preparatory commission’s cross to bear from the very first moment of our work, and now remains—like a crown—my cross.” Bugnini was completely unqualified to sit in judgment of magnificent scholars like Monsignor Higinio Anglés (d. 1969), who was responsible for publishing the complete works of Father Cristóbal de Morales. In a 2013 interview, Cardinal Bartolucci told Wilfrid Jones about Bugnini: “Much of the responsibility for what happened to the liturgy after the Council is his, and he often worked to promote his personal ideas.”

![]()