THIS PAST SUNDAY, I decided to write a brief response in the Gregorian Rhythm Wars series. I did this because Patrick recently issued an ultimatum together with several questions, mostly aimed at Jeff. I tried very hard to answer the questions with good humor, and I dashed off a response. In reality, only one of the questions had any real weight to it: the question of whether there is evidence from before the year 1100 for the singing of rhythms in Gregorian chant with something other than a duple proportion between long and short notes.

I have to admit now, a few days later, that my answer really has not sat well with me. I offered some general skepticism about the use of theoretical treatises for performance practice and also mentioned my experience singing from a triplex edition that morning. I stand by what I said about that chant, although I did not look at the original source (L) until the next day, which changed my opinion about some things. I also left much unsaid that I think is very important. For those who are still following this debate, I would very much like to offer a brief clarification of my point as well as a statement of the spirit in which I hope we can proceed.

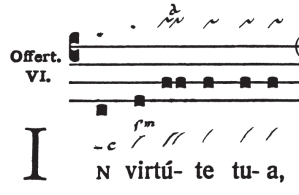

First, one point that I think argues strongly for the probability of nuanced rhythm in Gregorian chant is the great variety of signs. This is the point I was attempting to make on Sunday, and I wish I had made it more broadly. I would like again to refer to experience. Today I sang an all-Gregorian Mass in the New Rite, for the memorial of St. Vincent de Paul. In the wonderful offertory chant, there is a figure that happens many times, ascending from C to F in an inviting and intonational kind of way:

Now this figure gives us quite a bit of differentiation between L and E (the two sources, above and below the square notes). I believe that if Patrick were to follow E here, every syllable set with a single note (except for the first one or two) would have a long note, and furthermore, these long notes would all be of identical length with each other. But if Patrick were following L, all the syllables with a single note on either C or D would be sung with a note of exactly half the time value of the others. In the case of the accented syllable following this little ascent, they all consist of a full two long beats (or perhaps we should say a dactylic foot) consisting either of Long-Long or Long-Short-Short. This is all well and good, and it may even be correct. But it makes all of the rhythmic letters (“t” and “a”) and all of the episemata redundant. This may well be correct, but one reason why many of us find the mensuralist approach reductive is that it fails to account for the great variety of rhythmic signs here.

A little bit later, we get the very clear case of the multiple sizes of virga in L, which is probably much clearer than the point I was trying to make about the uncinus on Sunday. I believe that even Patrick is willing to go outside of the 2:1 proportion in this case. Perhaps one could be even more free!

If I were a follower of the Cardine method (rather than a mere student and admirer of that method looking in from the outside) approaching the first four examples, surely the salient point here is that we have an ascent to the accented syllable (indeed the tonic accent in every sense of that word), and the signs given by the neumes are mere aids to uttering those words in a convincing way.

Why am I singling out this point? Because one beautiful aspect of the Cardine approach here is that it can harmonize the two manuscripts quite convincingly. If I take the word rhythm (rushing toward the tonic syllable and placing the high note on it), I might well sing the music the same whether I am taking L or E as my basis. And it leaves me free to pronounce the words differently, while taking account of the various signs. Perhaps the a in the first example in L suggests that I should stretch the -tu– of virtute. Perhaps the t in the last example means that I should hold the first F a bit more. The signs become aids to an interpretation that also places the words and their pronunciation first.

My second point is about the spirit in which I want to make these arguments. I alluded to this a bit in my last post, but I would like to make it as plain as possible right now. I do not know if Cardine was correct about everything. I’m sure that I am not correct about everything, and I’m also pretty confident at this point in my reading that Mocquereau was not correct about everything. But something about the way the Rhythm Wars series has gone, it seems that there is some suggestion that some ways of singing chant are just correct, full stop. I’m afraid this attitude has occasionally even verged on the edge of a want of charity. I have consistently argued for pluralism precisely because I do not believe this to be the right way to approach the question. I do not want to condemn anybody for the way they sing chant. The important thing is to get them singing it in the first place! Tolle, lege, canta!

This does not mean that we forego our artistic judgment or our reason. I am happy to teach people the Solesmes method, the pure Vatican, mensuralism, equalism, and semiology; I have done all of those things in many different contexts and to people at all levels. I’m also, within my calling as a teacher, committed to meeting people where they are and improving their chanting. This is very, very important to me. But if I were ever to claim, while teaching, that such and such a way is the only correct way and that the others are definitely not correct, I would have to suspend my scholarly judgement, which teaches me to see many sides to this very difficult problem, especially as one digs into the neumes in the early sources of the Mass propers. There has been a certain amount of claiming to be correct in this series, and to the extent that I am participating in the “war” at all, it is in favor of seeing multiple plausible interpretations. There is very little from the medieval evidence that Vollaerts and Murray read or examined that was not also read or examined by Cardine and Mocquereau. What conclusion does that lead to?