Gregorian Rhythm Wars contains all previous installments of our series.

Please refer to our Chant Glossary for definitions of unfamiliar terms.![]()

ORE THAN NINE MONTHS AGO, Charles Weaver made the observation that, “Interestingly, for a chant rhythm war between a proportionalist and a proponent of the ‘pure’ Vatican rhythm, both parties seem to spend a great deal of time attacking Dom Mocquereau.” It was not the first time I’ve been accused of attacking Dom Mocquereau, and it probably won’t be the last. Someone else, having misunderstood what I wrote, came very close to claiming that I had slandered the man. Let’s be reasonable. A claim that a scholar misinterpreted evidence, with no insinuation of deliberate deception or otherwise malicious intent, should not be construed as an attack on the person. He likely acted in good faith, but that doesn’t mean he was right. I named the nuance and ictus theories as the basic faults with the Solesmes method; naivety and ignorance of the alternatives allowed those erroneous theories to be accepted widely, though not universally, throughout the Latin rite. Whether he intended to do so or not, Charlie has exposed two even more fundamental errors behind the Solesmes approach to rhythm: the application of the thirteenth-century “golden rule” and a historically implausible understanding of the nature of the tonic accent. Their interpretation of the so-called golden rule blinded both Mocquereau and Gajard to the clear evidence of Laon 239, which writes long notes in a non-cursive fashion, thereby dispelling any ambiguity concerning the number of notes affected by an episema in the St. Gall manuscripts, and their conception of the Latin word accent as high, short, light, arsic, and independent of the ictus, predisposed them against the steady tactus of proportional rhythm. “The independence of the Latin tonic accent and the rhythmic ictus has always been and will always remain the foundation and the basis of the Solesmes Method” (Mocquereau, tr. Weaver).

ORE THAN NINE MONTHS AGO, Charles Weaver made the observation that, “Interestingly, for a chant rhythm war between a proportionalist and a proponent of the ‘pure’ Vatican rhythm, both parties seem to spend a great deal of time attacking Dom Mocquereau.” It was not the first time I’ve been accused of attacking Dom Mocquereau, and it probably won’t be the last. Someone else, having misunderstood what I wrote, came very close to claiming that I had slandered the man. Let’s be reasonable. A claim that a scholar misinterpreted evidence, with no insinuation of deliberate deception or otherwise malicious intent, should not be construed as an attack on the person. He likely acted in good faith, but that doesn’t mean he was right. I named the nuance and ictus theories as the basic faults with the Solesmes method; naivety and ignorance of the alternatives allowed those erroneous theories to be accepted widely, though not universally, throughout the Latin rite. Whether he intended to do so or not, Charlie has exposed two even more fundamental errors behind the Solesmes approach to rhythm: the application of the thirteenth-century “golden rule” and a historically implausible understanding of the nature of the tonic accent. Their interpretation of the so-called golden rule blinded both Mocquereau and Gajard to the clear evidence of Laon 239, which writes long notes in a non-cursive fashion, thereby dispelling any ambiguity concerning the number of notes affected by an episema in the St. Gall manuscripts, and their conception of the Latin word accent as high, short, light, arsic, and independent of the ictus, predisposed them against the steady tactus of proportional rhythm. “The independence of the Latin tonic accent and the rhythmic ictus has always been and will always remain the foundation and the basis of the Solesmes Method” (Mocquereau, tr. Weaver).

Dom André Mocquereau, O.S.B. (1849–1930)

Outdated Scholarship • For almost any chant of the Proper of the Mass, the Solesmes notion of the golden rule can be disproved by comparing the neumes copied in a triplex edition; the only way around that problem is either to claim that the neumes mean something different than what they obviously do, which was Mocquereau’s approach, or to claim they’re irrelevant, which is Ostrowski’s approach; indeed, he never acknowledges a long note at a syllabic break because he disregards the rhythmic indications of the oldest sources altogether. As for the nature of the stressed syllable in Latin, the tonic accent, I’m unaware of any current scholarship supporting the idea that the Latin language still had a pitch accent by the Early Middle Ages, when the chants were composed. Admittedly, this is outside of my areas of expertise and interest, but what I’ve read indicates that classical Latin had vowel quantity (which I learned from Mrs. Sims in tenth grade) plus a pitch accent not necessarily coinciding with a long vowel, both of which died out sometime in late antiquity. It was anachronistic and incorrect to apply the characteristics of classical Latin to the medieval Latin of Gregorian chant. The Church learned this lesson the hard way with the 1631 “reform” of the Office hymns under Pope Urban VIII, now generally regarded as a huge mistake. Maybe there are scholars still claiming today that Carolingian Latin had vowel quantity and pitch accent, but they aren’t in the majority, and it is probably fair to say that there is a scholarly consensus to the contrary. Charlie mentioned that discussion of the importance of stressed syllables as pitch accents “has become a complete non-starter within the scholarly discussion of chant.” Although the term tonic accent remains in use, Latinists have overwhelmingly abandoned the idea of pitch stress in medieval Latin in favor of dynamic stress. Mainstream chant scholarship has moved on as well, yet the obsolete theory of the tonic accent as a pitch accent remains a basic underpinning of the classic Solesmes interpretation, as is evident in the quote above from Mocquereau. This is exactly the kind of thing I previously referred to as outdated scholarship, to my colleague’s vehement objection, but I would be happy to receive correction from a better educated reader if my understanding of the nature of the Latin accent in the Middle Ages is deficient according to solid evidence or current scholarship.

By What Authority? • The value of Mocquereau’s work as a whole is beyond question, but his ictus placement theory has now been discredited for more than six decades, and not even the most uncompromising champion of the Solesmes method today would seriously attempt to defend his salicus interpretation on paleographic grounds, as Charlie has admitted. Let us hope that the present decade will see the demise of the nuance theory, which still inexplicably allures semiologists, in favor of a return to the proportional rhythmic indications of the oldest extant sources. No further proof is needed for any sensible musician to reject the Solesmes misinterpretation of the thirteenth-century “golden rule” as inapplicable to the rhythm of the first-millennium chants. Throughout the Gregorian Rhythm Wars series, I have consistently implored my readers to study the oldest sources themselves to verify whether my claims are true. Although I have occasionally appealed to common sense and general musicianship, I have never asked anyone to take my word for anything. Jeff Ostrowski, on the other hand, attempts to buttress his position with irrelevant curial decrees from eleven decades ago, but let’s take a look at his Guillaume Couture Gregorian Chant draft. On the very first page of the actual chants, we encounter these markings:

Jeff, how are your additions licit according to the same criteria by which you pass judgment on Mocquereau? (#1) I have knowingly made an ad hominem attack here, but my objection remains valid because you yourself raised the same issue with regard to Mocquereau’s editions. A few pages later:

But compare the Vatican edition:

Jeff has omitted the liquescent figures. Another example:

With such additions and omissions, surely anyone using his edition must incur the anathema of Cardinal Roche’s predecessor! But in all seriousness, how are all of his markings and alterations fine if Mocquereau’s (and mine) are supposedly absolutely forbidden? It is difficult to fathom how adding a dotted line straight through all four lines of the staff is permissible but writing a dot after a note is out of the question. Something doesn’t add up here.

Examples • For the mode IV antiphons, I have prepared a very short comparison for the monastic version, which leaves no doubt as to the correct rhythm:

A reasonable interpretation of the monastic version of the antiphon Propheta magnus:

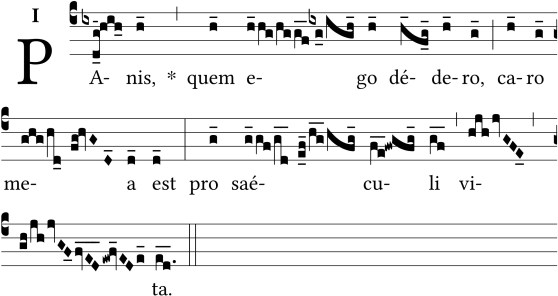

For the Communion Panis, quem ego dedero, here is the version from the Graduale Triplex:

My interpretation:

Verify for yourself that the edition above adds rhythmic markings without altering the typography of the Vatican edition—which is more than can be said for Jeff’s editions. Assuming that the prohibition against altering note spacing is a “dead letter” (and I’m not the one arguing otherwise!), consider whether the following improves both accuracy and legibility:

Here’s a recording:

If you find my recording aesthetically lacking, I suggest making your own in the same style. Why not? We see from these examples that the problem with Mocquereau’s interpretation lies in what he omitted, not in what he included—or, as Jeff says, added.

Challenge Accepted! • Jeff has written more than once that Mocquereau “had a predilection for a handful of manuscripts,” or similar words. In fact, the manuscripts in that handful are among the oldest and best. In his first post in this series, Jeff nicknamed them “Moc’s Fantastic Four.” Their value is so widely acknowledged by serious chant scholars and their rhythmic indications now well enough understood that it takes a dilletante to place them on an equality with nonrhythmic manuscripts from later centuries, but here we are. To the extent that Mocquereau interpreted some things correctly, I suppose I’m stepping forward to defend him. Jeff asks, “what if every single editor had mutilated the official edition according to a handful of manuscripts for which they [sic] had fondness? Does anyone doubt what the result would have been?” Are these merely rhetorical questions? I honestly can’t tell! Besides the Solesmes and triplex editions, I know of only seven rhythmic editions of the Sunday Mass Propers produced in the past forty years, namely those of Hakkennes, Blackley, Stingl, Kainzbauer, Turco (example page), Nickel, and my own. Five of those are predicated on the nuance theory. Jeff can compare the results for himself, but what will he compare them to? The pure Vatican edition? The Solesmes edition? Laon 239? Einsiedeln 121? St. Gall 359? Chartres 47? Bamberg 6? Montpellier H. 159? Some beautifully illuminated but rhythmically insignificant Gradual from the fourteenth century? Well?? To the extent that Mocquereau relied on first-millennial manuscripts in preference to later sources, I’ll take the witness stand again in his defense. What are we to make of Jeff’s irrelevant claim that no one can “prove” that the oldest extant sources are, in fact, the oldest? He might as well ask me to “prove” that I’m the real Patrick Williams and not a clone. Where would I even start? (And if I were a clone, wouldn’t I be able to offer the same “proof” anyway?) This is really getting ridiculous. The burden of proof is on the one who persists in ignoring the evidence.

Jumping to Some Conclusions and Avoiding Others • Why should it matter if the Hook & Hastings organ in the Cathedral of the Holy Cross was built in 1776, 1875, or 1974? Are there not older extant instruments? Are there not bigger, more versatile, more expensive, or more beautifully voiced organs elsewhere? Aren’t there other organs from 1875 that are almost nothing like that one? Has no other musical instrument besides the Hook & Hastings organ ever been played in the Cathedral of the Holy Cross? Didn’t Hook & Hastings themselves build other organs that were quite different from it? Why should anyone think that it is representative of Hook & Hastings organs, late nineteenth-century American organs, or Catholic cathedral organs? Have you ever heard of a Hook & Hastings organ in the Vatican? On the stop list, I see an Open Diapason in all four divisions, but many other organs have a stop called Principal. Some spell it Prinzipal, others have just a plain Diapason without the adjective Open, and still others have a Montre, Prestant, or something else instead. What makes you think those are just different names for the same kind of stop? How can you be so sure? And don’t say, “because Audsley and Gleason say so!” Supposedly, over 275,000 Hammond B3s were produced. That surely must count for something, right? Wouldn’t it make a lot more sense to take the Hammond B3 as an example of a typical American organ? They play all right, don’t they? And guess what? Hook & Hastings closed the same year Hammond set up shop, 1935. It’s true! It must mean that Hook & Hastings suddenly forgot how to build pipe organs as soon as electronic organs were developed. . . . I have deliberately made quite a few non sequiturs in the preceding sentences to prove a point, but I’ll let Jeff figure out for himself what it is. I hope you got some amusement from this little diversion, but I’m fed up with playing games instead of having serious discussion about the rhythm of the oldest extant manuscripts, and I think many of our readers are growing weary of it as well. Don’t let Jeff pull the wool over your eyes again! In his first post, he dated seven manuscripts to the ninth or tenth century: St. Gall 359, Bamberg 6, Laon 239, Chartres 47, Einsiedeln 121, Mont Renaud, and Montpellier H. 159. Now he has the gall (pun intended!) not only to question whether they are truly that old but also to claim “that we know very little about when these manuscripts were created.” Ladies and gentlemen, this takes the cake. He’s making things up as he goes along. Why doesn’t he admit defeat already? Could it be any more obvious that he is avoiding discussion of the rhythm of those sources by invoking unsourced historical claims, personal tastes, a misleading and inconsistent interpretation of the law (which he conveniently disregards in his own editions), and the concept of unprovability pitted against a nebulous notion of tradition?

Ignoring Vollaerts and Misrepresenting Cardine • Jeff asks, “Why were these crucial and esteemed manuscripts [Einsiedeln 121, St. Gall 339, St. Gall 359, and Bamberg 6] not copied?” but then in his next paragraph, apparently with no awareness of the contradiction, he proceeds to tell us that scribes continued to copy the St. Gall neumes long after adiastematic notation had fallen out of fashion elsewhere. If Jeff had bothered to read the Vollaerts chapter I recommended in my first post in this series, he wouldn’t be asking about the copying of St. Gall manuscripts. As I wrote in my fifth reply, “This has nothing to do with scribes no longer understanding how to write the older notation, but it doesn’t make much sense to continue differentiating long and short notes on the page once they’ve all become equal in performance,” which is precisely what can be observed from comparing the later St. Gall manuscripts to the oldest ones.

St. Gall 379, Thirteenth Century

St. Gall 353, Thirteenth or Fourteenth Century

Jeff’s unwillingness to do his homework, some ten and a half months later, demonstrates that he’s not sufficiently familiar with the subject matter and therefore unqualified to participate in the type of serious debate I signed up for. Why invite someone to discuss the rhythm of the oldest extant manuscripts and then argue that those sources are no more valuable than “thousands” of others, on the pretext that nobody can prove their exact dates? If the situation weren’t bad enough already, he attributes to Cardine the idea that “the authentic rhythmic tradition was lost because the copyists ‘tried to represent the melodic intervals more exactly.’” Unsurprisingly, there’s a real comprehension problem here, and Jeff loses more credibility with each new post in this series. What Cardine actually wrote is that “the interpretive particularities and the finesse of the notation gradually disappeared as a result and before long they came to write all the notes in an identical way.” Jeff has twisted Cardine’s words in order to portray a gradual process as a sudden alteration. My opponent is correct, however, in saying that “there was not a ‘sudden rupture’ in the manuscripts at Saint Gall” and that “the scribes continued to use adiastematic notation long after it fell out of fashion.” Who exactly has claimed otherwise? Not Cardine, not Mocquereau, and not I!

Questions Remain • Jeff, please tell us: Who claims that there was a sudden change to the chant rhythm? (#2) As far as I can tell, you’re attacking an argument that nobody has made. Suppose, for the moment, that Wagner, Mocquereau, Gajard, Vollaerts, Cardine, Murray, and practically all chant scholars of the modern era are correct in accepting that a gradual decay of the authentic traditional chant rhythm took place in the eleventh century, all across Europe, in which the tempo was slowed down and the note values were evened out. According to the accepted historical narrative, it was the singers themselves who changed the rhythm. The scribes wrote what was actually sung; they did not cause the rhythmic decay by changing the notation. As a thought experiment, pretend that you also accept that narrative as factual. Now, I ask you: Is it helpful to know that a given manuscript is from the tenth century, before the change, even if the exact year can’t be pinpointed? (#3) Again, assuming such a change took place, would it be reasonable to expect a manuscript from the end of the eleventh century to show the same rhythm as the one from the tenth? (#4) How about one from the thirteenth century? The ninth?

US-NYcub Western MS 097, Thirteenth Century

For the fifth time: Do you believe that there was a sudden change of the Protestant chorales and psalm tunes, from rhythmic to isometric? (#5) Why or why not? (#6) For the fourth time: Is it “miraculous” that Old Hundredth is sung with the same melody today as in 1551? (#7) For the third time: Are the 1791 or 1854 versions of Old Hundredth adequate to reconstruct the rhythm of the the 1565 version? (#8) And the million-dollar question: Is there any evidence for “nuanced” rhythm, totally outside the 1:2 proportion, from before the year 1100? (#9) Why do you hold the opinion that the long marks of the oldest manuscripts were nothing more than “slight nuances, probably intended for individual cantors,” which agree with each other only by accident? (#10) Show us some evidence. It’s time to quit pussyfooting around and either answer my ten questions directly or else concede. Enough is enough, and our readers deserve better!