ICHARD J. CLARK recently appeared on a spectacular video—which has already received 13,000 views—exploring the pipe organ at his cathedral in Boston. I hope Mæstro Clark will share more with us in the coming weeks. The pipe organ played by Richard each Sunday was built in 1875. Believe it or not, it’s basically identical to how it was back then (although some pipes have been replaced over the last 148 years). This gargantuan pipe organ was constructed just ten years (!!!) after the Civil War ended. I mention this because my article today is about the rhythm of plainsong. Many will exclaim: “These days, so many bishops and cardinals are flagrantly scandalizing the faithful and even denying fundamental tenets of the Gospel. Is it really appropriate to be worried about plainsong rhythm?” But surely Catholics in Boston in 1875 said: “Should we really be worried about glorifying God in our worship in these times? Should we really be exerting all this effort to assemble a massive pipe organ for our cathedral in light of all the atrocities that just took place in the Civil War?” Dom Pothier lived through many wars, but that did not stop him from peacefully going about the work of Gregorian restoration.

ICHARD J. CLARK recently appeared on a spectacular video—which has already received 13,000 views—exploring the pipe organ at his cathedral in Boston. I hope Mæstro Clark will share more with us in the coming weeks. The pipe organ played by Richard each Sunday was built in 1875. Believe it or not, it’s basically identical to how it was back then (although some pipes have been replaced over the last 148 years). This gargantuan pipe organ was constructed just ten years (!!!) after the Civil War ended. I mention this because my article today is about the rhythm of plainsong. Many will exclaim: “These days, so many bishops and cardinals are flagrantly scandalizing the faithful and even denying fundamental tenets of the Gospel. Is it really appropriate to be worried about plainsong rhythm?” But surely Catholics in Boston in 1875 said: “Should we really be worried about glorifying God in our worship in these times? Should we really be exerting all this effort to assemble a massive pipe organ for our cathedral in light of all the atrocities that just took place in the Civil War?” Dom Pothier lived through many wars, but that did not stop him from peacefully going about the work of Gregorian restoration.

Mocquereau’s Modifications (Added) • In the front of every copy of the official edition, with the date of 14 August 1905 assigned to it, a special decree was printed. To publish this decree, Pope Saint Pius X called upon the legendary Luigi Cardinal Tripepi (1836-1906). This proclamation explicitly said the EDITIO VATICANA was to be:

“considered by all persons as the standard or NORM, so that henceforth any Gregorian melodies contained in future editions of these books are to be made absolutely uniform with the aforesaid standard, without any addition or omission…”

Consider the official edition of the MAGNIFICAT ANTIPHON for last Sunday:

![]()

Now consider the version published with “rhythmic additions” by Prior André Mocquereau:

How did Mocquereau’s version conform to the 14 August 1905 decree by the Congregation of Sacred Rites? We already examined (above) the decree, which said: Nihil prorsus addito, dempto vel mutato, adamussim sint conformandae, etiamsi agatur de excerptis ex libris iisdem. Translated into English, that means when it comes to the EDITIO VATICANA “absolutely nothing may be added, removed, or changed.” Monsignor Francis P. Schmitt, writing in 1960, described the situation as follows:

In the very beginning the Solesmes camp set upon a series of rhythmic signs. And there is a bit of history about this: The Solesmes Kyriale, 100,000 of them, appeared about the same time as the Vatican’s, and with the same approbation. The rhythmic signs so interfered with the musical text, which the Vatican had declared inviolate, that it drew this rejoinder from Cardinal Merry del Val: “The official commendation attached to the Desclée books through a misunderstanding has been immediately withdrawn. In the circumstances the copies already printed need not be recalled, but the official stamp will not be affixed to any succeeding printings.”

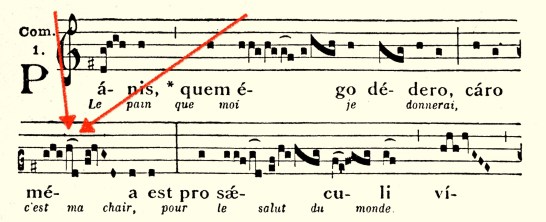

Mocquereau’s Modifications (Deleted) • But Dom Mocquereau didn’t just add elongations where none belong; he also deleted elongations which were supposed to be there. Consider the COMMUNION ANTIPHON from last Sunday, as printed in the official edition. In any melisma, blank space “equal to the width of a note-head” indicates a required mora vocis (elongation). For a 2-note neume, both tones are usually lengthened:

![]()

The official edition was based upon the 1883 Liber Gradualis, created by Dom Pothier at Solesmes Abbey. We can see there was no shortage of “blank space” in the original:

![]()

Dom Lucien David, the private secretary and biographer of Abbat Pothier, created a special edition in 1932 which used tiny markings to remind the singer about the moræ vocis. Are your eyes sharp enough to see the little mark? It looks like the letter “U” upside down:

![]()

Those who follow the official edition mark the elongation. Consider the same passage as harmonized by Father Mathias in 1909:

![]()

Max Springer’s 1912 edition follows the official edition, so he marks the elongation (although it’s not easy to understand why he didn’t lengthen both parts, since it’s a 2-note neume):

![]()

The 1909 Schwann edition in modern notation correctly marks the elongation:

![]()

The 1940s edition by the Lemmensinstituut correctly indicates the mora vocis, but leaves it up to the individual choirmaster whether to elongate both notes of the 2-note neume or only the final:

![]()

Now, let’s consider the edition by Dom Mocquereau, which frequently introduces elongations which don’t belong while eliminating elongations that ought to be there:

![]()

Judge For Yourself:

Here’s the direct URL link.

![]()

Target Practice • Do you agree that the version by Mocquereau is like “target practice” for the singer? Try recording yourself, and notice how awkward it is without the elongations intended by the creators of the official edition.

I Can’t Go Back • I sang from the Mocquereau editions for decades. Year after year, we sang the full propers (including the full Gradual and full Alleluia) at every Mass. But I was always curious about the official rhythm. For decades, I didn’t have the guts to make the switch. But the more I learned about the rhythm that was intended by the creators of the EDITIO VATICANA, the more uncomfortable I became with the thousands of illicit modifications by Dom Mocquereau. I eventually realized there’s no comparison between the official rhythm and Mocquereau’s rhythm from (an aesthetic point of view). I’m afraid I can never go back!

Argument #1 (AESTHETIC) • Is it not logical to sing the edition as it was intended to be sung by its creators? We looked at the MAGNIFICAT ANTIPHON for last Sunday and saw that Dom Mocquereau’s illicit modifications made the melody become heavy and plodding, whereas Cantus Gregorianus should be light and flowing. We examined the COMMUNION ANTIPHON and saw how Mocquereau’s illicit modifications wrecked its beauty, as if the singer were there to conduct “target practice” with pitches instead of creating coherent phrases.

Argument #2 (LAW) • For those who desire to adhere to the traditions (and liturgical laws) of 1962, singing from the official edition created by Pope Saint Pius X—without illicit modifications by Dom Mocquereau—seems inescapable. For myself, the “argument from authority” pales in comparison to the aesthetic argument (above). Moreover, I have already illustrated this point in so many blog articles, it would be inappropriate for me to be labor it here.

Argument #3 (MS. TRADITION) • In the rhythm wars series, I have tried to explain why Mocquereau’s actions were silly and indefensible. He had a predilection for a handful of manuscripts. He then brazenly took certain elements from those manuscripts and (according to his particular interpretations) modified the official edition. Is anyone willing to step forward and defend his actions? Many people, myself included, have a predilection for certain manuscripts. But what if every single editor had mutilated the official edition according to a handful of manuscripts for which they had fondness? Does anyone doubt what the result would have been? Dom Mocquereau had a few manuscripts he really liked—but he ignored the existence of thousands of other ancient manuscripts. Such a decision is reprehensible. Is anyone willing to defend that?

Some have put forward the idea that Dom Mocquereau preferred the manuscripts which were “oldest.” But no one can prove those manuscripts are older than all others. My colleague, Patrick Williams, has often cited the opinions of scholars who estimate that a certain MS might have been created in the “10th century.” But that hardly tells anything! Or, wait … perhaps I said that wrong. The fact that scholars (after all these centuries) still can’t agree as to whether a particular manuscript dates from 901AD or 999AD tells us an awful lot! Specifically, it tells us that we know very little about when these manuscripts were created.

Let’s pretend the handful of manuscripts which Dom Mocquereau preferred are slightly older than some others. That’s still no excuse to ignore thousands of ancient (and important) manuscripts. Indeed, if someone tries to place the “oldest” manuscripts in opposition to those created a few years later, one must ask: “Why were these crucial and esteemed manuscripts not copied?” In other words, if they were so important that every other manuscript was basically “garbage”—as many today claim—why did the immediate descendants not deem them worthy of copying?

In his 1982 book, Dom Eugène Cardine claims (page 8) that the authentic rhythmic tradition was lost because the copyists “tried to represent the melodic intervals more exactly.” He gives absolutely no evidence whatsoever to support such a claim. To put it mildly, a multitude of problems confront Cardine’s theory. A few that come to mind instantly would include:

(1) Cardine’s theory flies in the face of contemporary evidence, such as the manuscript tradition at the monastery of Saint Gall. In my previous articles, I have given examples demonstrating there was not a “sudden rupture” in the manuscripts at Saint Gall. On the contrary—and this makes certain people very uncomfortable—the scribes continued to use adiastematic notation long after it fell out of fashion.

(2) Does it really makes sense that all the scribes throughout Europe would suddenly decide to preserve with unspeakable accuracy the melodies yet completely butcher the rhythm? Was there a memo sent out to everyone in Europe telling them: “Starting on Monday, we’re going to abandon the traditional rhythm entirely. However, please take great pains to reproduce the pitches with perfect accuracy.” Is anyone willing to defend such a notion?

(3) Let’s pretend such a “memo” was sent out. How on earth could it reach anyone? There was no email, no telephone, and no automobile. The computer would not be invented for another thousand years!

(4) Let’s pretend this “memo” (written by whom?) was somehow sent to everybody circa 1050AD. Why would anyone obey it? Surely there would be rebels somewhere who would keep doing the “authentic” rhythm. They might say to themselves: “We aren’t going to pay any attention to this memo telling us to preserve the pitches with tremendous accuracy but completely mangle and spoil the traditional rhythm.”

(5) Even if everyone suddenly decided (as Cardine claims) to mutilate the traditional rhythm yet somehow preserve with great accuracy the pitches, rhythm is not easy to banish from the mind. Rhythm is intimately connected with melodies. Dr. Charles Weaver, during Sacred Music Symposium 2022, publicly made the claim that rhythm is “more important” than the pitches. I’m not sure I’d go that far, but nobody would deny there’s a strong connection between rhythm and melody. Cardine’s theory is impossible because even if everyone suddenly decided to wreck the rhythm but keep the pitches, I’m absolutely convinced some scribes would have made mistakes. In other words, they would have accidentally used the “traditional” rhythm in certain places. That is to say, they would inadvertently have left us “remnants” or “testaments” or “examples” of this alleged authentic rhythm.

Article Summary • I begin today’s article reminding all of us (myself included) that we must peacefully focus on the work God has called us to do, never allowing ourselves to be scandalized by bishops and cardinals who fail to live up to the Catholic Faith. Then I tried to describe why I feel plainsong should be sung according to the official rhythm, which—and this is not disputed—was the rhythm intended by those who created the EDITIO VATICANA. Then I gave a video example which hopefully demonstrates the official rhythm is better aesthetically. Finally, I provided three basic reasons I favor the official rhythm.

Bookmark: Gregorian Rhythm Wars contains all previous installments of our series.