Gregorian Rhythm Wars contains all previous installments of our series.

ABLO CASALS (a famous cellist) lived until the age of 97. When he’d reached his nineties, a reporter asked why he still practiced six hours each day. Casals replied: “Because I think I’m making progress.” Patrick, in your fourth response to me, you threatened to abandon our exchange. You feel I’m not carefully reading your responses, which frustrates you. I can certainly understand somebody getting frustrated, especially if that person feels he’s becoming repetitious. Nevertheless, I do feel we’re making progress. Of course, you may excuse yourself from our conversation at any time … but I encourage you not to do so, because you might change your mind. Perhaps it would be better if you take a “pause”—rather than leave entirely.

ABLO CASALS (a famous cellist) lived until the age of 97. When he’d reached his nineties, a reporter asked why he still practiced six hours each day. Casals replied: “Because I think I’m making progress.” Patrick, in your fourth response to me, you threatened to abandon our exchange. You feel I’m not carefully reading your responses, which frustrates you. I can certainly understand somebody getting frustrated, especially if that person feels he’s becoming repetitious. Nevertheless, I do feel we’re making progress. Of course, you may excuse yourself from our conversation at any time … but I encourage you not to do so, because you might change your mind. Perhaps it would be better if you take a “pause”—rather than leave entirely.

Not Embarrassed • Twenty years ago, I had the opportunity to conduct a week-long interview with Dom Cardine’s former boss. My preparation involved tons of materials dealing with adiastematic neums. As I’ve said before, I don’t claim to be an expert on every single ancient manuscript—and I’ve forgotten much over the years. Am I embarrassed about this? No, because (as I’ve stated in the past) one who examines manuscripts carefully understands that each manuscript has its own peculiarities. On page 16 of his book, Cardine admits that many neums are complicated and mysterious, even in MSS he’s examined for decades!

Ronnie Knox • Suppose somebody tried to impress me by saying: “Jeff, I’ve dedicated my entire life to studying 857NOYON|1057. I’ve noticed its scribe sometimes writes such-and-such a neum a little bit squiggly, whereas other times he forms it less squiggly.” I would not be impressed. I don’t believe God is calling us to dedicate our lives to stuff like that. Such a person should instead have dedicated his life to teaching others how to sing Gregorian Chant, how to praise God with it, and how to understand the prayer behind it. As Ronald Knox said: “The scholar who lives only for his subject is but the fragment of a man; he lives in a shadow-world, mistaking means for ends.” I’ve never claimed to be the world’s greatest scholar on (for example) 339SANGALL|1039. My studies of plainsong have been dedicated to the entire repertoire, not one particular manuscript.

Let’s Get Down To Business! • Patrick, your article backed up with evidence a correlation vis-à-vis the “non-cursive clivis” among a few ancient manuscripts. I consider your presentation to be praiseworthy, and I’m grateful to you. Am I surprised by it? Not really, because (as I’ve said many times) the ancient manuscripts without question are based upon a single ‘source’ or tradition. Only a very foolish person could look at the miraculous correlation between the various manuscripts—and remember, we’re talking about hundreds of thousands of notes—and pretend that somehow the same melody ended up all over Europe in an age when travel was virtually impossible, there was no internet, there was no telephone, illiteracy was widespread, and most people never set foot outside their town. So what was the original ‘source’ or tradition? Perhaps my question wasn’t phrased properly so let me try again: What precisely was the original ‘source’ or tradition? Whether it was a book, or whether it was transmitted orally, or whether it was some combination of both remains a mystery. But if someone discovered a musical manuscript from the 5th century that survived somehow, such a discovery would shed light on this question!

Who Cares About “Non-Cursive” Clives? • You have proven there’s a correlation among some ancient manuscripts vis-à-vis the non-cursive clivis. Now comes the tricky part: why does that matter? The rest of my article will explore that precise question.

We’ve been considering 47CHARTRES|957. How old is this manuscript? Susan Rankin of the University of Cambridge (perhaps the most respected authority on these matters) in her 2018 book claims it was created “somewhere in western/central France circa 900.” David Hiley dates it “circa 900.” Father Eugène Cardine simply says “10th century.” On 16 May 2023, I spoke about the inherent difficulties of assigning dates to ancient manuscripts. I don’t want to get sidetracked by repeating all that—so let’s stipulate arguendo that 47CHARTRES|957 was created (perhaps) circa 957AD.

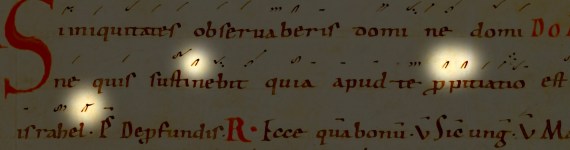

Patrick, you have designated this neum found in 47CHARTRES|957:

You correctly pointed out there’s a correlation with three other manuscripts: (1) 239Laon|927; (2) 121EINSIE|961; and (3) Bamberg6LIT|905. Those manuscripts probably sound familiar to readers, owing to my article dated 1 November 2022. If you have a moment, go back and read what I wrote vis-à-vis “Moc’s Fantastic Four.” Here’s the same passage as it appears in Bamberg6LIT|905:

For good measure, we can include 342SANGALL|933, which may (perhaps) have been created circa 933AD—but that’s just a guess on my part, since different parts of that manuscript date from different periods:

No Explanation Provided • Patrick, you correctly noted that 339SANGALL|1039 does not match the others—yet you offered no explanation. That manuscript seems (perhaps) to have been created around the year 1000AD, and notice how it uses both forms of the clivis:

![]()

What Does This Mean? (1 of 2)

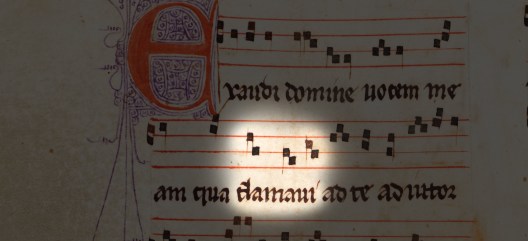

So what does this correlation mean? To find out, let’s examine an INTROIT sung a few weeks ago, on the 5th Sunday after Pentecost. Below is how it appears in the official edition (“Editio Vaticana”) published in 1908 by the Vatican Commission on Gregorian Chant—established by Pope Saint Pius X—under the direction of Abbat Pothier:

Mocquereau Modifies! • Dom André Mocquereau spent many years preparing a special Liber Usualis which appeared in 1904, shortly after Pope Saint Pius X issued his famous document on sacred music (“Inter Pastoralis Officii”), dated 22 November 1903. The rhythmic markings in Dom Mocquereau’s 1904 book were based on a handful of manuscripts, for which he had a predilection. When the official edition was published, mandated by Col Nostro (25 April 1904), Dom Mocquereau had no interest in discarding his special project. Therefore, he added symbols on top of the official edition, even though this was forbidden (since his symbols contradicted the rhythm of the Editio Vaticana). Here’s Mocquereau’s version, which became quite popular:

The President Speaks • Abbat Pothier, president of the Vatican Commission on Gregorian Chant—in his famous “de caetero” letter—said the modifications added by Dom Mocquereau “constitute a grave alteration of the notations, inasmuch as these supplementary signs have nothing traditional about them, and they do not even have an exact relation with the famous ROMANUS signs of Saint Gall, a reproduction of which they claim to be. Even if they were faithfully reproduced, these latter rhythmic signs—belonging to a particular school—have no legal right to force themselves on the universal practice, as it is intended by the typical and official edition.”

Dom Mocquereau believed that a clivis with episema meant there should be an elongation on the first note. Those who look at 339SANGALL|1039 will understand why Dom Mocquereau added the modifications he did:

![]()

Stumbling Blocks! • We run into trouble, however, when we examine 338SANGALL|1058. This manuscript was created (at least according to some sources) circa 1058AD. We can see that it marks a clivis with episema once, leaving the other two as a “normal” clivis. In other words, it does not match 339SANGALL|1039:

Another manuscript from the self-same monastery, created (perhaps) in 1074AD, is 374SANGALL|1074. It does not match 339SANGALL|1039:

Now let’s consider RENAUD|965, a very important manuscript which (perhaps) was created around the year 900AD. As far as I can tell, all three instances of the clivis do not match 339SANGALL|1039:

Another important manuscript, 47CHARTRES|957—which we spoke of above—seems to indicate a non-cursive clivis for two neums, but a cursive clivis for the third. Therefore, it does not match 339SANGALL|1039:

One of the most important manuscripts is MONTPELLIER H. 159, the “bi-lingual” manuscript, created around the year 990AD. It does not match 339SANGALL|1039:

Let’s now consider YRIEIX|1040, a very important manuscript which is also called Graduale, Troparium et Prosarium ad usum Sancti Aredii. (The sixth-century saint “Aredius” is also known as “Saint Yrieix.”) It does not match 339SANGALL|1039:

Now let’s consider 857NOYON|1057, which is currently held in the British Museum. It was created (perhaps) around the year 1057AD. It does not match 339SANGALL|1039:

Now let’s examine HAUTCRETABBEY|1120, from Switzerland. Copied during the 13th century, this manuscript replicates a manuscript created around 1120AD. It does not match 339SANGALL|1039:

To add some variety, let’s examine a Dominican Missal from 1275AD. It does not match 339SANGALL|1039:

Enough is Enough! • I would gladly post a billion more manuscripts, but “enough is enough.” Let’s close with HELMST|1026, created (perhaps) around the year 1026AD. It does not match 339SANGALL|1039:

![]()

![]()

What Does This Mean? (2 of 2)

I’ve attempted to create a chart, showing our results:

* PDF Download • COMPARISON CHART (“Clivis with Episema”)

—Jeff prepared this, based on his understanding of what Patrick said.

Adiastematic Contradiction • Thanks to my staggeringly brilliant disquisition (above), everyone must now acknowledge that it’s incorrect to say: “The earliest adiastematic neums correspond to one another perfectly.” Susan Rankin, considered by the academic world to be an expert in these matters, wrote as follows on page 170 of her 2018 book (Writing Sounds in Carolingian Europe, Cambridge University Press):

“It is worth insisting on this: in graphic terms, these regionally defined notations have a much higher degree of similarity than of difference.”

A False Claim • By considering even a minuscule amount of evidence, we see how reprehensible it was for Father Eugène Cardine to claim on page 9 of his book (Gregorian Semiology, 1982) that the Saint Gall manuscripts present an “imposing and obviously coherent testimony.” The earliest adiastematic manuscripts simply do not match. However, we can truthfully declare: “We do possess a handful of manuscripts that—when it comes to so-called ‘rhythmic’ indications—show more similarity than difference.” I’m aware that whenever discrepancies are demonstrated, lazy scholars blame SSS (“Stupid Sloppy Scribes”), but that puerile cop-out is becoming harder and harder to fool people with, since so many manuscripts are now available online. Another reprehensible statement was made by Dom Gajard in 1952:

“One thing is certain. Up till nearly the middle of the 11th century, Western Christendom was in unanimous agreement not only as regards the melodic line but also as regards the expression or rhythm.”

Saint Gall School? • It would be disingenuous for one to claim fluency “in every single European language” if (in fact) one could speak Lithuanian only. I admit it sounds more impressive to say one can speak “every single European language”—whereas saying “I speak Lithuanian only” doesn’t sound impressive. Consider the school of Saint Gall. Many authors shamelessly pretend the entire collection of Saint Gall manuscripts match one another (regarding so-called ‘rhythmic’ indications). The truth—as we’ve seen above—is that when certain people make reference to the “school” of Saint Gall, they actually mean a minuscule percentage of the school of Saint Gall. For example, it is blameworthy for Dom Gajard in his book (The Rhythmic Tradition in the Manuscripts, 1952) to make reference to different “schools.” In the following quote, when he says “Metz” he actually means one particular manuscript only: viz. 239LAON|927:

“Wherever at Saint Gall the short form is seen, the short form is likewise found at Metz and at Chartres; wherever, on the contrary, Saint Gall gives the long form, the long form is what we find at Metz and Chartres in spite of the variety of notation.”

They Were Probably Nuances • How can we explain the discrepancies? I have suggested that many of the so-called ‘rhythmic’ indications were probably nuances. Therefore, when scribes ignore, jumble, or modify them, it’s no big deal.

300 Year Gap? • I realize some people claim that on a certain day (perhaps 1055AD?) every Catholic in Europe changed—fundamentally and irrevocably—the rhythm of plainsong from “mensural” to “equalist.” If there were an LLL (“Lavishly Large Lacuna”) that lasted 300 years, I could understand folks making that case. But there’s a monumental problem with such an assertion: the so-called ‘rhythmic’ manuscripts coexisted alongside the ‘non-rhythmic’ manuscripts. Indeed, we’ve seen manuscripts (above) from the same monastery, created within a few years of each other, which jumble the so-called ‘rhythmic’ signs. That’s why it’s silly to say scribes were “forced” to abandon mensuralism when the notes began (at first) to be heightened and (later on) placed on staves. In other words, adiastematic manuscripts changed to diastematic concurrently.

They Were Not Slaves to the Score • To put it another way, those who argue for a fundamental rhythmic change act as though the singers were reading from notes, meaning if scribes suddenly changed the rhythm, they were stuck. But they were not reading from notes; they were singing melodies they knew by heart! The adiastematic notation was similar to a “mnemonic device,” since the tradition was so reliant on memorized melodies. When it comes to explaining why all the so-called ‘rhythmic’ symbols were abandoned Dom Gajard—in his entire book—does not even attempt to provide reasons for this supposedly massive, fundamental, and irrevocable rhythmic change that (we’re told) magically occurred all throughout Europe. It’s quite incriminating, in my humble opinion, that Dom Gajard doesn’t offer a single reason why why such a massive change happened. On the other hand, if the so-called ‘rhythmic’ signs were very slight nuances—and perhaps references to other items, such as whether the melody went upwards or downwards—their gradual (pardon the pun!) disappearance presents no great problem.

“Ad Hominem” • Now that my article is over, Patrick, I desire to briefly address something you said. Specifically, you said I made an “ad hominem” attack on you vis-à-vis bringing up the topic of how many singers subscribe to your interpretations. I would like to say that (in my view) the question of how many singers follow a particular interpretation is not an “ad hominem” attack. On the contrary, it seems a very natural question, about which many would be curious.

Next Question • Patrick, I have another question I hope you will consider answering. As you know, there are often numerous ways used by scribes to indicate the self-same figuration, similar to how in modern music one can write the word cresc. or place a hairpin. What evidence is there that the following sign (cf. the red arrow) denotes—pardon the pun!—a longer note?

OR THE DURATION of this series, I’ve been obsessively focused on providing manuscript evidence supporting every notion I propose. Might I now be permitted a few concluding thoughts? Consider Dom Gajard’s book (The Rhythmic Tradition in the Manuscripts, 1952) or Dom Murray’s book (Gregorian Chant According to the Manuscripts, 1963) or Dom Cardine’s book (Gregorian Semiology, 1982). The authors of those books make the staggering claim that they understand the true rhythm of Gregorian chant much better than monks from the same monastery just a few years later, who (we are told) totally corrupted the rhythm.

OR THE DURATION of this series, I’ve been obsessively focused on providing manuscript evidence supporting every notion I propose. Might I now be permitted a few concluding thoughts? Consider Dom Gajard’s book (The Rhythmic Tradition in the Manuscripts, 1952) or Dom Murray’s book (Gregorian Chant According to the Manuscripts, 1963) or Dom Cardine’s book (Gregorian Semiology, 1982). The authors of those books make the staggering claim that they understand the true rhythm of Gregorian chant much better than monks from the same monastery just a few years later, who (we are told) totally corrupted the rhythm.

Ask Yourself This! • Is it plausible that someone like DOM GREGORY MURRAY—separated by 1,000 years—understands the “authentic rhythm” better than monks separated by just a very few years? In some cases, the so-called ‘non-rhythmic’ manuscripts may even pre-date the so-called ‘rhythmic’ manuscripts. For instance, Montpellier H. 159, according to current scholarship, was created circa 990AD. That’s before Einsiedeln 121 (which Cardine calls “11th century”) and Bamberg6 (which Cardine dates circa 1,000AD), and Saint Gall 339 (which Cardine dates as “11th century”). Montpellier H. 159 is fascinating because it contains the precise names of the notes (letter names) right underneath the adiastematic notation! And in the article above, we examined manuscripts from the school of Saint Gall which use two forms of the clivis, yet in a way contradicting 359SANGALL|877. Therefore, I don’t understand why some claim the “authentic rhythm” became corrupted or forgotten because scribes “could no longer properly write adiastematic neums.” Patrick, I’d welcome hearing from you (and Dr. Weaver) regarding the evidence I’ve assembled.

Clarification • Using shorthand, I have referred to that theory as the “mass hallucination” theory. Perhaps that was a dumb way to describe it. What I was trying to say, was this: somebody needs to explain to me how everybody in Europe could suddenly “forget” or “corrupt” the true rhythm. Why did such a thing happen? Patrick, you have suggested I don’t pay attention to what you write—but I’d encourage you to say it again as clearly as you can. A famous proverb from Singapore says: “There is no student who cannot learn, only a teacher, who cannot teach!”

Forcing the Shoe to Fit • My dad used to say: “If all you’ve got is a hammer, everything starts looking like a nail.” Scholars like Dom Mocquereau seemingly determined their theory in advance—based on a handful of codices they really liked—then spent the rest of their time trying to ‘force’ all other manuscript evidence to fit that theory.

![]()