E ARE SOMETIMES ACCUSED accused of being “obsessed with the practical,” because we’re so focused on providing survival techniques for fledgling choirs. I do feel that church music is experiencing a deep crisis, and God wants us to help turn things around. Indeed, the recent release of the Brébeuf hymnal is all about practical solutions for real parishes. But today, we release a book of tremendous scholarly importance: the 1908 Editio Vaticana of the Roman Gradual with Solesmes rhythmic markings.

E ARE SOMETIMES ACCUSED accused of being “obsessed with the practical,” because we’re so focused on providing survival techniques for fledgling choirs. I do feel that church music is experiencing a deep crisis, and God wants us to help turn things around. Indeed, the recent release of the Brébeuf hymnal is all about practical solutions for real parishes. But today, we release a book of tremendous scholarly importance: the 1908 Editio Vaticana of the Roman Gradual with Solesmes rhythmic markings.

* PDF Download • 1908 Graduale Romanum

—1,077 pages; 96.6MB; with Solesmes rhythmic markings.

In 2008, I allowed the CMAA to scan my personal copy of the “pure” 1908 Gradual, but I also wanted to see a copy with Solesmes rhythmic markings. I have been searching for this book for twenty years. The book is 112 years old, so you’ll find some pencil markings:

I’ve often claimed that not a single ictus marking has been changed since 1908, and now I can backup my claim. However, occasionally ictus markings were added. Do you see how additional ictus markings were added in 1957 to make things more explicit?

Throughout the entire book, the Capital letters are absolutely exquisite, and I don’t understand why Solesmes later abandoned their use:

You can find several pages that were inserted later. For example, Propers for the Sacred Heart were changed in 1929 under Pope Pius XI, but you can still see the version from 1908, which is fascinating:

Below, I attempt to explain the book’s deep significance, and why you should be excited about this release!

T IS NOT EASY to know where to begin the story of the 1908 Graduale Romanum. Let me say briefly that Cantus Gregorianus is far and away the first music we can know with certainty. (Mark that last part: “with certainty.”) We have a “trail” leading back to the 8th century which is certain beyond a doubt—it is not guesswork. That’s because of the way many different MSS from many different countries correspond: the adiastematic MSS, the MSS “in campo aperto,” the “heightened” neumes, the Red Line Fa Clef, and so forth. We talk about all that at the Sacred Music Symposium, so let’s skip ahead from the 8th century to the 16th century, when Gregorian chant reached a low point. At that time, instead of drawing MSS by hand, people began to use the same “printed notes” that were being used for polyphonic music. (Printing was still relatively new at that time.) Naturally, singers began to corrupt the rhythm of the chant, because they were used to the rhythm of polyphony. Consider this excerpt from the Directorium Chori of Father Giovanni Guidetti:

T IS NOT EASY to know where to begin the story of the 1908 Graduale Romanum. Let me say briefly that Cantus Gregorianus is far and away the first music we can know with certainty. (Mark that last part: “with certainty.”) We have a “trail” leading back to the 8th century which is certain beyond a doubt—it is not guesswork. That’s because of the way many different MSS from many different countries correspond: the adiastematic MSS, the MSS “in campo aperto,” the “heightened” neumes, the Red Line Fa Clef, and so forth. We talk about all that at the Sacred Music Symposium, so let’s skip ahead from the 8th century to the 16th century, when Gregorian chant reached a low point. At that time, instead of drawing MSS by hand, people began to use the same “printed notes” that were being used for polyphonic music. (Printing was still relatively new at that time.) Naturally, singers began to corrupt the rhythm of the chant, because they were used to the rhythm of polyphony. Consider this excerpt from the Directorium Chori of Father Giovanni Guidetti:

This is what is called “corrupt” chant: (1) in its mensuralist rhythm; (2) in its tonality; (3) in its shifting the melismata to accented syllables only. With regard to the rhythm, Father Guidetti specifically says:

(The mensuralist approach is starting to experience a revival of sorts, but that’s another story for another day.) A very popular edition in the 17th century was that of Guillaume-Gabriel Nivers, an organist who lived in Paris. Notice how corrupt it is, with the sharps and flats distorting the tonality:

Another popular edition was called the Editio Medicæa, published in 1614 by the students of Palestrina. In the 19th century, the Editio Medicæa was printed in a new edition by Monsignor Franz Xavier Haberl, and this “corrupt” edition received approbation from Pope Pius IX. In fact, it was awarded a 30 year “papal printing privilege,” causing many bishops to adopt it for their dioceses. Here is a sample page of the Medicæa, as reprinted by Monsignor Haberl in 1871 (thanks to Friedrich Pustet, a Regensburg printer):

The Pustet/Haberl team taught singers to use “mensural” rhythm when singing plainsong. Haberl’s axiom was “sing as you speak”—that is, sing the chant as you would speak it:

Here is a Haberl/Pustet accompaniment from 1892, according to these principles:

…which corresponds to the (1871 “corrupted”) plainsong notation:

Monsignor Haberl wrote a book called Magister Choralis, which went into twenty editions! In that book, Haberl provides this transcription:

You are probably thinking: “That sounds extremely complicated.” It is complicated, and we observe this complexity in thousands of organ accompaniments, such as this 1874 example:

However, this time period (the middle of the 19th century) was also when important plainsong discoveries were being made, and such discoveries came to the attention of a young monk of Solesmes Abbey named Joseph Pothier. The most important discovery was a manuscript called Montpellier H. 159, which is also called the “Faculty of Medicine Manuscript” because it was lost amongst medical manuscripts until it was “discovered” by a French organist named Jean-Louis-Félix Danjou. The manuscript is very ancient—approximately 10th century!—and includes the note names for all to see:

That meant that ancient adiastematic notation such as this:

…could henceforth be compared in a meaningful way to later MSS such as this:

In fairness, Dom Pothier was not the only one looking at ancient MSS, trying to improve the corrupt editions popular at that time, such as the Pustet Medicæa reprint, the Mechlin edition, the 1858 LeCoffre, and the Reims/Cambrai edition. Father Michael Hermesdorff of Trier was working diligently—until his death—to produce a more faithful edition. Observe how Father Hermesdorff included the adiastematic notation (and Romanian letters!) in his 1876 Gradual:

It is somewhat curious that nobody considered using a remarkable 1853 edition published in Paris. I will give you an example of its excellence:

Finally, in 1883, Dom Pothier—while still a monk of Solesmes—released his magnificent “Liber Gradualis” (a.k.a. Graduale Romanum). The notation, the typsetting, the images, and the restored melodies took the world by storm:

The editions of Pothier became quite popular all over the world, and they got a very “friendly” letter from Pope Leo XIII dated 8 March 1884. Solesmes made sure to use this letter to their advantage, carefully printing it towards the front of all their books. The special “papal printing privilege” of the Medicæa expired in December of 1900. In 1901, Pope Leo XIII wrote an even stronger letter supporting Solesmes, called “Nos Quidem.” Dom Pothier (d. 1923) had been sent away from the Solesmes monastery to become Prior of the Ligugé community. Then, in July of 1898, Pothier had been appointed Abbot of Saint-Wandrille. Pothier’s student, Dom André Mocquereau (d. 1930) had basically taken over his duties at Solesmes.

The Reform Under Pope Pius X

When Cardinal Sarto was elected pope in 1903, things began to move rapidly. Just four months (!!!) after choosing the name “Pius X,” the new pope issued extremely bold decrees with regard to Sacred music. On 22 November 1903 came Tra le sollecitudini, by far the most audacious church music legislation ever promulgated. Then, on 25 April 1904, Pope Pius X issued another Motu Proprio, which specifically appointed a committee—Abbot Pothier was named president, with Mocquereau and others underneath him—to create the official edition: the mighty Editio Vaticana. It is important to note that in 1903, Mocquereau had published his life’s work: a new edition of the Liber Usualis which he considered a tremendous improvement over Pothier’s editions. Between 1900 and 1905, Mocquereau and many other members of the Pontifical Commission (such as Dr. Peter Wagner) were publishing plainsong books at a frighteningly furious rate. I’ve never understood how they were able to release such a massive amount of books during those crucial years.

So much was happening at that time! For example, in 1901, the Solesmes monks had to move from France to England (the Isle of Wight) due to French anti-clerical laws. And in March of 1904 was held the “Gregorian Congress” in Rome, with 800 members in attendance, totally thrilled about the “new” chant books appearing. On 11 April 1904, Pius X celebrated a solemn Papal Mass in the Vatican Basilica. A choir of 1,210 voices from 36 different Roman colleges and institutions sang the Ordinary (Kyrie and Gloria VIII, Credo III, Sanctus and Agnus IX) under the direction of Don Antonio Rella. A schola of 150 Benedictines from San Anselmo sang the Proper under their Rector, Dom Janssens. We can actually hear recordings made during this 1904 congress, for example: (1) Abbot Pothier conducting Augustinians in the Gaudeamus; (2) Monsignor Antonio Rella breaking into song during his speech; (3) Dom Mocquereau conducting the Easter Sunday Introit from his newly published 1903 Liber Usualis. Please ignore the silly warning added by the recording catalog: “It cannot be denied that these Gregorian Chant records are somewhat monotonous, except to those especially interested.”

Everything seemed to begin well in 1904, but the Papal Commission quickly became divided: the followers of Mocquereau (who was now Prior of Solesmes) vs. the followers of Pothier (including Janssens, Gastoué, and Wagner).

Essentially, what was happening was that the supporters of Dom Mocquereau—instead of working on creating the new edition—were spending their energy trying to force Pope Pius X to get rid of Dom Pothier, so that Dom Mocquereau could take his place as President of the Commission. (That’s a simplified version of events.) I have read many of the letters from that time, and—in my humble opinion—several of the Mocquereau’s supporters come across as naïve and jealous. Pope Pius X couldn’t stand all the bickering and secret maneuvering, so he ordered Cardinal Merry del Val to write a letter dated 24 June 1905. In this letter, the Cardinal informed the commission that, effective immediately, the books by Pothier were to serve “as the basis” for the Editio Vaticana. Abbot Pothier had won, but Dom Mocquereau would get his revenge.

“Invisible White Notes”

There’s an old saying: “You can win the battle, but lose the war.” It’s true that Pothier’s editions served as the basis for the Editio Vaticana. Under the presidency of Pothier, the Papal Commission published the Kyriale in 1905, the Cantus Missae in 1907, the Graduale Romanum in 1908, the Officium pro Defunctis in 1909, the Cantorinus seu Toni Communes in 1911, and finally the Liber Antiphonarius in 1912. Since 1913, the creation of new books (such as the Cantus Passionis in 1916 and the Officium Hebdomadae Sanctae in 1922) has been entrusted to the monastery of Solesmes. Pope Pius X died on 20 August 1914.

We must understand something called “invisible white notes.” Even after 112 years, very few musicians understand them. They are explained (with pictorial examples!) in the front of every Liber Usualis ever printed, but people always skip over these pages. Musicians alive back then were already accustomed to “invisible white notes” because Pothier had explained them in his Liber Gradualis of 1883:

The Editio Vaticana basically adopted Pothier’s “invisible white notes,” but changed a few things in a haphazard way that ended up giving Mocquereau his opportunity for revenge. One thing they changed was officially written on 29 June 1904 by the Papal Commission: “In the Vatican edition, the morae vocis shall be indicated by a blank space of equal and unchanging width, and four sorts of bars shall be used…” In other words, no matter how long or short the pause was supposed to be, they said they were going to leave a “uniform” distance…but they didn’t always follow through. (The “white notes” only apply to melismas—you must always remember that.) Another way in which they departed from the earlier editions of Pothier has to do with letter D in the following:

The instructions for Letter D are ambiguous. You can read about this ambiguity, and notice how Monsignor Francis P. Schmitt hits the nail on the head. At the end of the day, the person who wrote that Preface (Dr. Peter Wagner, according to Father de Santi) made an unforgivable mistake by introducing that ambiguity regarding the Virga.

The “invisible white spaces” are explained by Joseph Gogniat, a student of Dr. Wagner, writing 1939. Essentially, if there is enough “space” to fit a notehead, the singer is supposed to slow down (i.e. apply the mora vocis):

Did you notice where Gogniat talks about holding the book with your nose touching the spine (“at eye-level”) so you can tell whether the “white space” is large enough to indicate a mora vocis? Many people feel this is a ridiculous way to sing music—constantly having to worry about whether the “space” is equal to a notehead—but Abbot Pothier wanted clean scores leaving freedom for the musicians who would be interpreting the chant. Abbot Pothier also greatly feared that explicit rhythmic indications would tempt singers to perform the chant in a mechanical “paint-by-numbers” way. And he was correct to fear these results.

Gogniat continues his explanation, but “muddies the waters” (even though his intention was to clarify). Notice how he gives absolutely no explanation for how a neume can “depend upon” a Virga:

How Mocquereau Got His Revenge

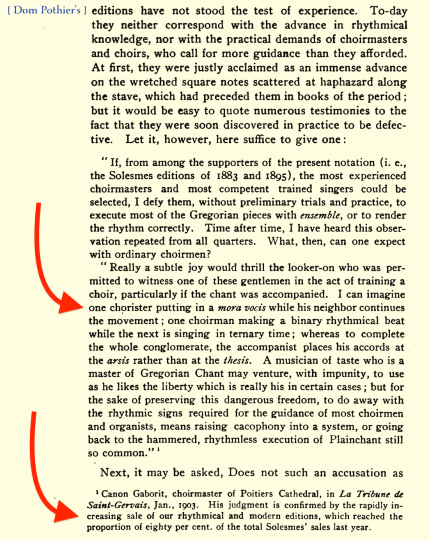

The rhythm of the Editio Vaticana was simply too confusing, and Dom Mocquereau took full advantage of this reality. Dom Mocquereau was opposed to the “invisible white notes”—and explicitly wrote as follows in December of 1905, in a Kyriale he published (the official title was: The Kyriale according to the Vatican Edition with Rhythmical Signs by the Monks of Solesmes):

A truly practical notation has to mark plainly every incisum, every phrase, every passage or period, and to indicate with exactness where the mora vocis should come. This is very important because the rhythm largely depends on the attention paid to these divisions.

Mocquereau thereby rejected and condemned the rhythmic freedom desired by Pothier, who had been his mentor at Solesmes. Writing in 1906, Dom Mocquereau called this freedom “dangerous” (his word!), while not denying this liberty technically does belong to the singer:

Please immediately download this critically important document:

* PDF Download • Mocquereau on “Invisible White Notes”

—Single page PDF with examples from 1905 (October and December)

That document makes it clear beyond a shadow of a doubt that Mocquereau rejected Pothier’s “melismatic morae vocis”—and who will deny that he had a point? There was confusion in melismatic sections. There was also great confusion over the most basic phrases, since the Editio Vaticana left this decision to the choirmaster:

Joseph Gogniat despised the Solesmes rhythmic signs with all his heart, and claimed he created a “simple system” that respects the official rhythm. But the system Gogniat came up with looks utterly preposterous:

Speaking of “preposterous,” when singing from the “pure” Editio Vaticana, one must instantly recognize how much “space” exists between the final note of a melisma and the tiny little Custos (a.k.a. “guide” or “sentinel”) at the end of the line. This is beyond absurd:

If you’re tempted to doubt what I say, read the official Vatican explanation dated 6 September 1906.

Proof The “White Notes” Are Ambiguous

Out of more than 12,000 possible chants, I will use just one to demonstrate why the rhythm of the Editio Vaticana is ambiguous. Specifically, we will be looking at the places in Kyrie V shown with Green Arrows:

The Editio Vaticana was not finished until October of 1905. If we examine the 1883 edition by Pothier, we see that he places the mora vocis at the second place only:

The same is true of the 1895 edition by Pothier:

The 1903 Liber Usualis published by Dom Mocquereau two years before the Editio Vaticana elongates both places:

Dr. Peter Wagner in 1904 elongates both:

We can be sure of this by comparing to the 1904 modern notation edition by Dr. Wagner:

Regarding the Gregorian editions by Dr. Wagner, Abbot Raphael Molitor wrote:

In other places, owing to the varying width of the space between the note-groups, it remains doubtful whether the editor really desired a mora or not. He seems to have felt this uncertainty himself when he wrote on p. VIII: De his omnibus rebus utile erit, transcriptionem in notas musicas modernas hujus libelli consulere. But what singer will buy a Kyriale when he finds he must purchase a second book as a key to the first? Even a choirmaster would scarcely do so.

Molitor wrote this to try to convince German musicians to abandon the editions of Wagner in favor of the Editio Vaticana. Dr. Wagner had been Pothier’s staunchest supporter, and I was shocked to discover that Wagner flagrantly contradicts the rhythm of the Editio Vaticana—which he himself produced!—in his 1905 edition:

When we examine this 1905 edition from Styria, we remember that the Vatican had not yet become strict with regard to the note shapes. That is why the notation looks somewhat odd, and not very elegant in my opinion:

The Schwann 1905 edition is exactly as we would expect—Editio Vaticana “pure” and simple:

In Dom Mocquereau’s 1905 version of the Editio Vaticana, notice how he changes the shape of several notes. This would be condemned by the Sacred Congregation of Rites in no uncertain terms soon thereafter:

Professor Amédée Gastoué was an enemy of Solesmes, so it is not surprising to discover he favors the “pure” Editio Vaticana:

Friedrich Pustet was a major rival of Solesmes—since Solesmes had ended his 30 year “papal printing privilege”—and his versions are “pure” Editio Vaticana. The neumes look slightly odd, but Pustet would abandon those aspects quickly thereafter:

In 1906, Schwann issued an edition in modern notation, and I am absolutely flabbergasted to see them flagrantly contradict the Editio Vaticana rhythm:

Dr. Franz Xaver Mathias (an Alsatian priest) was organist at Strasburg Cathedral, where he founded in 1913 the “Saint Leo Institute for Church Music.” Astoundingly, the version by Father Mathias also contradicts the official rhythm—although somebody has taken a pen and tried to “fix” the score to make it match Solesmes:

The version of the Editio Vaticana printed by the Vatican Press is (as we would expect) perfect and not surprising:

The version by Father Karl Weinmann (1909) is quite crisp and clear. It was a brilliant idea to place the chant on five lines, but seems to have been abandoned when the Vatican started “cracking down” on publishers who altered the note shapes. (Father Weinmann modified difficult-looking neumes, making them easier for beginners to read.)

This next example took me by surprise! Max Springer (an organist associated with Beuron Abbey) contradicts the official rhythm. I really have no idea why Springer does this, unless he was following Wagner’s lead:

In case you thought Dr. Mathias made a mistake above…think again! He sticks to his guns in 1912, and contradicts the official rhythm:

Monsignor Franz Nekes follows the “pure” Editio Vaticana exactly as it should be followed, with no surprises:

Solesmes contradicts the official rhythm in 1924 (as we would expect), and how can we blame them when so many others—who claim to follow the “pure” Editio Vaticana—commit the same violation?

Joseph Gogniat—a student of Dr. Peter Wagner—was the most ardent and ferocious defender of the “pure” Editio Vaticana, so we should not be surprised that he follows it strictly:

The Nova Organi Harmonia (NOH) followed the “pure” Editio Vaticana, and they mark the rhythm exactly as we would expect:

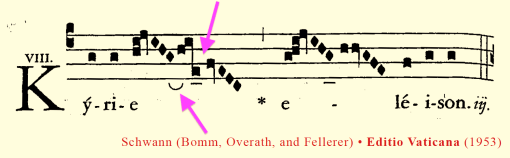

The 1953 Schwann version of the Editio Vaticana had three famous editors: Abbot Urbanus Bomm, Karl Gustav Fellerer, and Monsignor Johannes Overath. In the book’s Preface, the editors admit that determining the morae vocis is challenging. Therefore, they invented a system to help the singer. According to their system, the little line means “place a mora vocis” whereas the little hook means “do not place a mora vocis.” Those who carefully examine this edition will notice the editors often tell the singer to ignore the mora vocis for no reason at all. However, they treat Kyrie V exactly as we would expect from a “pure” Vaticana edition:

The vast majority of Catholics followed the Solesmes editions, since the rhythm was clearly marked. I could have included many examples of editions from the “Mocquereau school”—Bas, Guennant, Potiron, Desrocquettes, Lapierre, Bragers, and so on—but there was no need, since they all match the Solesmes rhythmic markings. If someone you meet knows a particular chant, they probably know it according to the markings in the 1908 Solesmes edition. Speaking of the 1908 Graduale, here’s how Kyrie V looks in this incredibly rare and precious book, which I hope you have already downloaded (above):

We have seen how confusing the “pure” Vaticana rhythm is. Some authors pretend there are no difficulties. For example, Father Dominic Johner (d. 1955) wrote in 1906 as follows:

It is certainly possible to emphasize the contradictions too much. After all, there is usually a manuscript somewhere that supports any approach, such as:

The Purpose Of This Article

I have attempted to explain why everyone should be excited we have made the 1908 Solesmes Graduale available for free PDF download. Over the next few months, I hope to add more information. I have only given you the tip of the iceberg. There is so much more.

Here is something Joseph Lennards (d. 1986) wrote:

For those who wish to sing Gregorian chant, a choice must first be made: The Vatican edition, or the Vatican edition with the Solesmes rhythmic signs? The Vatican edition with the rules contained in its preface is inadequate and leaves us in a fog. The well-known “white notes” that serve to indicate lengthening are difficult to find and are even an embarrassment to eminent Gregorianists. The rhythmic editions, on the contrary, are clear and precise.

That is how Mocquereau got his revenge on Pothier. Mocquereau was devastated when Pope Pius X chose Pothier’s editions as the basis for the Editio Vaticana, but soon thereafter, the “rhythmic” editions of Mocquereau became popular beyond anyone’s wildest dreams. Technically, the Solesmes editions are not allowed, because they contradict the official rhythm. (Cf. the letter of Cardinal Martinelli dated 18 February 1910.) On the other hand, we have seen that even the “pure” Editio Vaticana books contradict the official rhythm! [The Vatican specifically addressed these rhythmic signs on 14 February 1906, 18 February 1910, 25 January 1911, 11 April 1911, and 3 September 1958.] It is an odd situation, but after 115 years, musicians must simply accept reality.

In January of 1906, Abbot Pothier (responding to a letter from the organist Charles-Marie Widor) wrote as follows:

[The rhythmic signs of Dom Mocquereau] constitute a grave alteration of the notations, inasmuch as these supplementary signs have nothing traditional about them, and that they have not even an exact relation with the famous Romanus signs of St. Gall, a reproduction of which they claim to be. Even if they were faithfully reproduced, these latter rhythmic signs belonging to a particular school have no legal right to force themselves on the universal practice, as it is intended by the typical and official edition. […] I have seldom paid attention to polemics and rarely desired to take part in them. Nevertheless, you are authorized to make of these explanations the use you think opportune.

Dr. Peter Wagner called the rhythmic signs an “untraditional garment draped over the melodies.” For myself, I often find that Mocquereau’s rhythmic signs have a deleterious effect on the plainsong. Consider what Mocquereau did to this antiphon:

Often, you can see how hard the Solesmes monks had to work to add their (technically illicit) rhythmic signs without doing violence to the official notation:

Again, I refer the reader to this:

* PDF Download • Pothier’s 1906 “De Caetero” Letter

—Two English translations are provided.

Conclusions From This Article

Let me close by making a few observations:

(1) In 1905, nobody thought the Editio Vaticana would last more than 10 years. However, it has lasted 115 years and is still the official version of the Catholic Church.

(2) In my opinion, the “pure” Editio Vaticana is nicer than the Vaticana with Solesmes rhythmic signs. Pothier was correct when he worried that Mocquereau’s “nuances” would wreak havoc on the chants, making them heavy and plodding. Pothier was correct to desire freedom and subtlety for singers. However, Mocquereau’s version conquered, because Pothier’s rhythm was confusing and ambiguous. For the last 115 years, the Solesmes editions have become the traditional chant of the Church; this cannot be changed. It would be lunacy to attempt to restore the “pure” Editio Vaticana at this point.

(3) Pothier was correct that attempting to place the romanian signs of Saint Gall onto the Editio Vaticana makes no sense—because the Vaticana is a Cento. The Vaticana reflects the traditions of plainsong from many countries and many centuries; it does not pretend to be a reproduction of a particular monastery from a particular century. Furthermore, Dom Mocquereau did not apply all the romanian letters; he only applied some of them. To be absolutely clear, it makes no sense to place rhythmical “nuances” from a particular monastery or century over a Cento, and the Editio Vaticana is a Cento. In the 1980s, efforts were made (in certain quarters) to place rhythmic markings from a particular monastery onto the Editio Vaticana—but such an effort is flawed and indefensible because the Vaticana is a Cento.

(4) We can be certain that when we sing from the Editio Vaticana—even with Mocquereau’s rhythmic markings—we are singing the same basic melodies in the same basic way Catholics sang them for centuries. This is an awesome reality.

(5) I would like to thank Rene Widmann for donating the 1908 Graduale to be scanned. Also, the image of the Pontifical Commision was taken from one of the books by Fr. Robert Skeris. I should mention that Fr. Skeris has published several invaluable books about the monastery of Solesmes.