HAT I WRITE HERE, I write for myself, I am as guilty as anyone. Let me be direct: Disparagement of entire genres of music is not helpful to the cause of liturgical reform. It is deeply harmful. Oh, it may seem like fun among like-minded friends. This is what is called “intellectual incest” – to discuss ideas only among those with whom one agrees. It does not challenge one to grow spiritually or intellectually, no less musically.

HAT I WRITE HERE, I write for myself, I am as guilty as anyone. Let me be direct: Disparagement of entire genres of music is not helpful to the cause of liturgical reform. It is deeply harmful. Oh, it may seem like fun among like-minded friends. This is what is called “intellectual incest” – to discuss ideas only among those with whom one agrees. It does not challenge one to grow spiritually or intellectually, no less musically.

I have addressed this topic before in my “Proposed Lenten Fast for Musicians” that we abstain from hurtful and divisive language. Andrew Motyka has written one of the finest articles on the subject, “If the Shoe Fits” — a must-read.

Disparagement is not catechesis. Living by example is. Meanwhile, I recommend ridding ourselves of a few words often used to describe entire genres of music: “tawdry,” “banal,” “insipid,” “elitist,” “dreary,” “antiquated,” etc. These may very well apply to many individual pieces. They do not and never apply to entire genres.

To teach is a sacred trust. When we speak, write, and catechize about sacred music and the Vatican II Liturgy Documents, it is important to stay on-point, i.e., stick to the virtues of singing the mass, reverence, etc. There is no place for wholesale derision or disparagement to bolster an opinion. It weakens the argument. It weakens credibility. It is also entirely unnecessary. If we are to bring forth treasures new and old, music of lasting value will eventually speak for itself.

N RECENT MONTHS, TWO ARTICLES sparked much debate. I’m sure many of you have seen them. It began with Scottish Composer James MacMillan’s article “Too much Catholic church music caters to old hippies.” and Bernadette Farrell’s reply, “It’s not the composer’s place to denigrate worship styles.”

N RECENT MONTHS, TWO ARTICLES sparked much debate. I’m sure many of you have seen them. It began with Scottish Composer James MacMillan’s article “Too much Catholic church music caters to old hippies.” and Bernadette Farrell’s reply, “It’s not the composer’s place to denigrate worship styles.”

I am in fact sympathetic to both. James MacMillan, a formidable composer whose Saint John Passion was premiered by the London Symphony Orchestra, understands quite well the need to reclaim our badly neglected traditions. He points out his admiration for “curators” of our musical traditions who place the Word above style:

“The Americans seem to be ahead of the game and are producing new publications which enable the singing, in the vernacular, of those neglected Proper texts for Introits, Offertories and Communion. The creators of this music are curators of tradition more than ‘composers’, with all the issues of individuality, style and aesthetics attendant on the word. But what these curators are doing is remarkable.”

While he also stated that he will no longer write music for congregations, I would implore him that his frustrations – many that I share — should be the very reason he must compose more congregational music. While, his complaints may be true of many works, to apply them to all music of a certain genre is to reveal a lack of familiarity with its vast repertoire.

COMPOSER BERNADETTE FARRELL’S REPLY echoes this concern. Her final words drive to the heart: “It is not my place, and neither is it James Macmillan’s, to denigrate songs which enable people to pray, to celebrate hope, to grieve, to love and to follow Christ.” (emphasis added)

Like it or not, there is music we might not like that people find they can pray to. That cuts both ways. It is a difficult and often inconvenient reality for everyone. We often forget this isn’t about impressive musical programming but about prayer. I need reminding of this frequently.

Farrell also indicates correctly that “The Liber Usualis book of plainchant did not arrive complete from heaven; it evolved through centuries of human effort. The same is true of all music.”

Yet, all music is vetted over time. Fortunately, most hymn tunes in current use have been vetted for a century or more, and in the case of much Gregorian Chant, a millennia. For music written since Vatican II, we have not had adequate time to weed out what is unworthy. Twenty to thirty years from now, the perspective on music of this era will be far more clear, and the true treasures will remain. To think that there aren’t any is arrogance. Meanwhile, we must sort through it on our own.

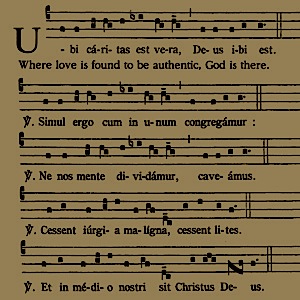

OWEVER, THERE ARE TWO COMMENTS by Farrell that require greater clarification. First is her assertion that “Every genre, including plainsong, includes good and bad examples.” If she is referring to new compositions of plainsong, then I agree. If she is referring to Gregorian Chant, then I disagree because the Gregorian Chant handed down to us has survived centuries upon centuries. It is imperative to note that Gregorian Chant is historically and uniquely different from other genres because it grew up side by side with the Roman Rite. That the mass is a sung prayer, Gregorian Chant was given birth by the Roman Rite itself. No other genre has such a distinction and therefore has pride of place for this very reason. It holds the same unique and historic place in worship as Greek Orthodox Chant, for example, or Cantillation, the ritual chanting of Scripture in the synagogue.

OWEVER, THERE ARE TWO COMMENTS by Farrell that require greater clarification. First is her assertion that “Every genre, including plainsong, includes good and bad examples.” If she is referring to new compositions of plainsong, then I agree. If she is referring to Gregorian Chant, then I disagree because the Gregorian Chant handed down to us has survived centuries upon centuries. It is imperative to note that Gregorian Chant is historically and uniquely different from other genres because it grew up side by side with the Roman Rite. That the mass is a sung prayer, Gregorian Chant was given birth by the Roman Rite itself. No other genre has such a distinction and therefore has pride of place for this very reason. It holds the same unique and historic place in worship as Greek Orthodox Chant, for example, or Cantillation, the ritual chanting of Scripture in the synagogue.

SECOND IS ONE I WHOLEHEARTEDLY agree with with spiritually, but needs a closer look professionally:

“What makes good liturgy? The Prophet Micah poses the same question: What worship does God require? And the answer has no solutions for the liturgy or music committee. No recipe. Only this: do justice, love mercy, and walk humbly with your God (Micah 6:8).”

We must approach our pastoral duties with justice, love, and mercy. However, that this is all there is glosses over the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy, no less over one hundred years of documents from the 1903 Motu Proprio, Tra le Sollecitudini (“Instruction on Sacred Music”) of Pope Saint Pius X all the way to the 2007 US Bishop’s document Sing to the Lord: Music in Divine Worship.

I suggest we combine the two approaches: that we catechize with regard to the liturgy and its documents keeping in mind the Prophet Micah’s instruction to “do justice, love mercy, and walk humbly with your God.”

OINCIDENTALLY, BERNADETTE FARRELL’S setting based on Psalm 139, “O God You Searched Me and You Know Me,” when sung properly with the full choral arrangement and organ accompaniment, could easily be mistaken for an anthem suitable for an Anglican Church. Her style seems to vary, but all of her music has symmetry and good form. Yes, I’m familiar with her work. It does not fall under the category of “insipid” or “banal.”

OINCIDENTALLY, BERNADETTE FARRELL’S setting based on Psalm 139, “O God You Searched Me and You Know Me,” when sung properly with the full choral arrangement and organ accompaniment, could easily be mistaken for an anthem suitable for an Anglican Church. Her style seems to vary, but all of her music has symmetry and good form. Yes, I’m familiar with her work. It does not fall under the category of “insipid” or “banal.”

If we are to catechize and evangelize, we must put God first, not our own preferences. Meanwhile, we must instruct, teach by example, and strive for the ideal. Keep it positive. Disparagement is not catechesis. It is destructive. I’ll try to remember that because I need to.