HIS SUMMER I taught a week-long music course for highschool students. As the week progressed, I brought in samples of music to listen to, pieces by Bach or Beethoven, Mozart or Palestrina, that would illustrate this or that aspect of what we were reading and discussing. Although a few of the students had clearly been exposed to such masterpieces before, I was struck (as I always am) by how many had never heard music like this. I have the same experience year after year, and I never get over the sense of amazement. The Western world has the most incredible heritage of music of any civilization that has ever existed or will ever exist, over a thousand years of musical glory, and for most of our contemporaries, it is as if the great composers had never even existed or written their great works.

HIS SUMMER I taught a week-long music course for highschool students. As the week progressed, I brought in samples of music to listen to, pieces by Bach or Beethoven, Mozart or Palestrina, that would illustrate this or that aspect of what we were reading and discussing. Although a few of the students had clearly been exposed to such masterpieces before, I was struck (as I always am) by how many had never heard music like this. I have the same experience year after year, and I never get over the sense of amazement. The Western world has the most incredible heritage of music of any civilization that has ever existed or will ever exist, over a thousand years of musical glory, and for most of our contemporaries, it is as if the great composers had never even existed or written their great works.

The bright side is that, after only a week together, nearly all these young people were excited about the music, ready to search it out and start listening to it. They asked me to write down the composers’ names and recommended recordings. It always makes me happy to do so, as I feel that I am spreading a little “sweetness and light” in an age characterized by inhuman darkness and philistinism.

But what is always most poignant is the experience of hearing young people say, after hearing chant and polyphony, something like this: “I have never heard such beautiful sacred music before. If only my parish would have music like that!” Or: “I suggested learning some chants to our choir director back at home, and she said chant was forbidden after Vatican II.” Or: “It’s really hard for me to pray at my parish, because of the drums and the clapping.” Or: “How can people be so stubborn about sacred music, when Vatican II clearly says chant should have pride of place, and then polyphony?” A comment like the last one always arises when we read and talk about the chapter on sacred music from Sacrosanctum Concilium—section 116 is a big eye-opener. Would that more people would read Vatican II’s documents to see what they actually called for.

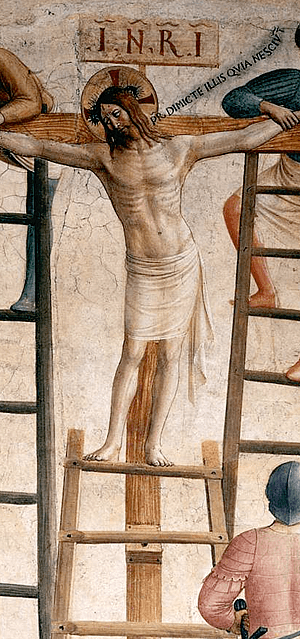

Within this conversation about sacred music, more poignant still is the reaction of the students when I play for them Antonio Lotti’s “Crucifixus á 8.” This work is a stunning portrayal of the Passion of Christ, enveloped in an atmosphere of resignation and tranquillity culminating in the final (pianissimo) major chord. In cascading layers of skilful dissonance, Lotti evokes the agony of our Lord; in one effortless cadence after another, he displays the peacefulness of the soul of Christ, resting in the Father’s will. It is a cathartic tour de force, all through the magic of music. How did the students react? They were rapt; they said it was gorgeous and painful at the same time. It was just what Lotti intended it to be: an experience of the Passion, a sonic icon. In my eyes as a teacher, it was an occasion of grace.

This is the religious experience, the subjective appropriation of the mysteries of Christ, that Vatican II intended the Christian faithful to be able to have as a regular part of their worship. It is a religious experience that most of the faithful have been denied for over forty years. I do not suggest that such an experience is identical to worship, but I do think it is a part of it and ought to be a part of it, in accordance with man’s nature as a rational animal, a thinking being with feelings, a sensual creature with a spiritual identity and vocation.

It is true that not every choir can manage an eight-part motet like Lotti’s, but it is no less true that this kind of composition could be sung regularly by cathedral choirs or well-trained ensembles at urban parishes, if only there were a director with good principles and a staff with open minds. Nor can we forget that there is an almost endless repertoire of simpler chant and polyphony to draw upon, as I have done for years with amateur choirs.

Whenever I listen to a work by Lotti or any master of sacred music, I cannot help thinking that the Church is like a dining room holding the most stunning plates, silverware, and glasses in its cabinets, and yet we are so often served our meals on styrofoam plates with plastic cutlery and paper cups. Perhaps the meal is the same, but what a difference it makes how the meal is served! People recognize the value of the food and drink far better when it is served in beautiful vessels and with loving attention to how the service is executed. The faithful by and large do not have a clue about the riches that belong to them, the riches that Vatican II said should be fostered and preserved with great care. Fortunately, those cabinets are still there, and while some of the precious contents have been discarded with contempt, much remains to be discovered anew.

It is more important than ever to educate a new generation of Catholics in the art of noble music and, in particular, the magnificent treasury of sacred music that belongs to us. We need to make more people aware of our great Catholic composers by talking and writing about them, and above all, by learning and singing their music at Mass. If we do not become missionaries for the beautiful, the beautiful will perish from our midst. Beauty, in the deeply resonant sense of traditional fine art, has already largely disappeared from popular culture, and, wherever it has not yet vanished from ecclesiastical art and ceremonies, it is on its way to disappearing. The fact that Pope Benedict XVI issued an invitation and a challenge that he underlined by example does not mean the crisis is over; it simply means that a way has been pointed out by which we can effectively overcome it. The crisis is obviously all around us, and most of the Catholic world seems to be living as if Pope Benedict had never uttered a single word of admonition, much less offered a single vibrant example of the correct ars celebrandi. In short, the work of renewal and restoration has just begun, and we must all play, to the best of our ability, whatever part the Providence of God has assigned us.